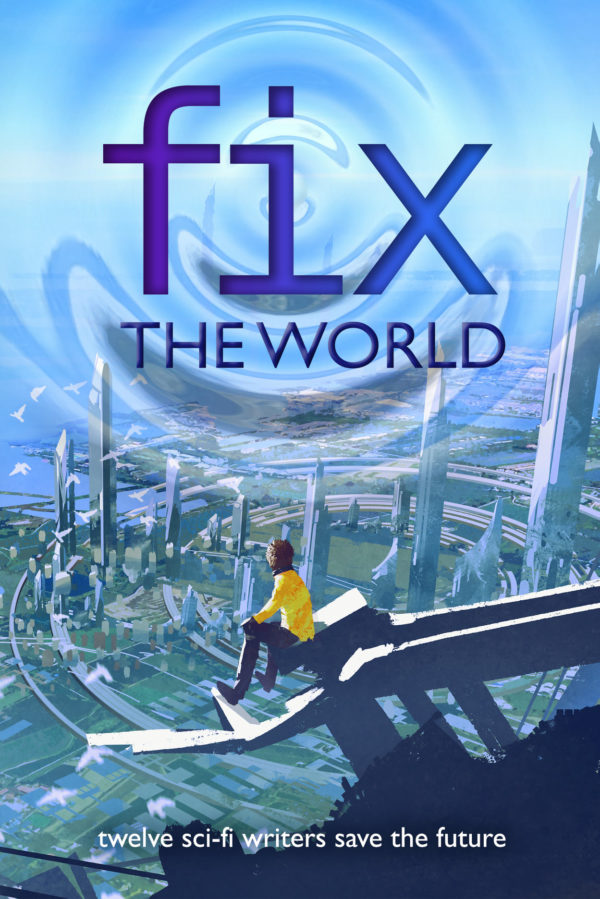

I’m relaunching The Weekly Fix, with a twist. For now, instead of a serial tale or a short story, I’m sharing excerpts from the stories in the forthcoming Fix the World anthology. This is a fantastic collection of twelve hopeful stories from sci-fi writers on how to fix some of the greatest problems we face as a world.

Who Shall Reap the Grain of Heaven?

J.G. Follansbee

Father James Bohm banked the SkyTrac T-44 crop duster over the abbey’s airstrip, feeling the mild tug of G-force on his broad shoulders and back. He never got tired of that sensation, almost like a hug from the heavens. The onboard AI smoothed out his nudges on the stick and the bumps through the thermals over the cornfields, making his piloting as smooth as silk. Like the Holy Father, though, it could override James if he erred too much, risking the plane or himself. James laughed at the image, though the sarcasm was too close to the truth.

James glanced to his left and behind the wing, glimpsing the dozen specially modified drones on the airfield below him. They were electric powered, like his own craft. He’d completed another job for the local corn and soybean farmers, spraying on batches of eco-friendly insecticides. The drones would soon take off on their own daily mission as part of the Seeds of Heaven project, if the Holy Father didn’t ground them first.

As James hooked the last of the tie-downs on his plane, patting the fuselage as if it were a beloved pet, a young, tonsured monk ran up to him. Dirt and oil stained the aircraft mechanic’s fingernails.

“Father, he’s here. Archbishop Mulvaney.”

James’s sense of well-being and accomplishment dissipated. Like a fulfilled prophecy, a day he’d feared had come.

“He’s brought a letter.” Elis sought reassurance from his abbot. “Is the project canceled?”

“Don’t worry. It’ll be all right.” He hid his disquiet from Elis. In fact, James wanted to climb back into the crop duster and take off. In the broad Midwestern sky, all problems on the ground shrank to nothing.

The men mounted their power-assist bicycles and pedaled down the airstrip’s main access road. A white, twin-engine passenger aircraft, also electric, waited near the drones. It had no markings, save for the registration number and the name Little Flower on the forward part of the fuselage. James would pilot the craft later in the afternoon.

Elis glanced over his shoulder, encouraging the head of the Abbey of St. Isidore to keep up. James took special care with Elis, because he was 19, and expected the results James could not always deliver. He might have to disappoint him.

Despite his fit body, James felt his 60s creeping up. The smell of fresh-baked bread cheered him, but when the chapel’s bell tower rose behind a screen of century-old trees, the knot in his stomach tightened. As a reminder of the ancient privileges of hierarchy, the archbishop had parked his black car in the abbot’s reserved spot.

James found Mulvaney in his office. After breathing cabin air infused with machine oil, James welcomed the whiff of incense. “Your Excellency, I’m sorry I wasn’t here to greet you.”

Mulvaney’s blue eyes betrayed his Irish heritage. “Any chance at a cup of tea?”

Elis took the hint.

“A good man, Elis.” Mulvaney’s eyes twinkled. “Youngest son of our state’s junior senator. Potential for great influence in Washington.”

Elis also had the potential of taking over as abbot, if James could follow through on his promise to keep the Seeds of Heaven project alive.

Mulvaney took in James’s short-sleeved jump suit. “Business must be good.”

Business was terrible, and Mulvaney knew it. The on-going drought hurt the farmers more than ever. “A few of our customers are still drawing water from their wells or the river. They’re the only ones who can buy our services.”

“They’re lucky to have you.”

“Fortunately, we can employ some of the others in Seeds of Heaven.”

The archbishop turned away at the project’s mention. The prelate looked at his hands, nervous.

“I’m afraid I have some news, James. You won’t like it.” Mulvaney reached into his jacket, removed an envelope, and handed it to James. His Holiness’s seal in gold ink decorated the embossed paper.

James already knew what the letter said: Stop the project. Perhaps the outcome was preordained, and he had failed to recognize the fact. Staring at the paper, James imagined that many of his 23 abbey brethren would applaud the order. When the contract with Victor Baran first came to him three years ago, he asked his community’s thoughts. They accepted it via an advisory vote, but only just. James also consulted the nearby convent of the Sisters of the Holy Cup, which also supported him. He signed the contract with Baran’s foundation, believing it was the right thing. The Vatican thought differently.

“Rome is done with scandal, James. It’s been a generation since the sex scandals, but we’ve never recovered. Catholicism is comatose in Europe, and its dying here in America. Even the Latin countries are falling away.”

James’s Mexican grandmother would disagree, if she were alive. Her fervor for her faith infected her grandson. He wouldn’t be at the abbey if it weren’t for her. “The Church is stronger than you think, Charlie.”

“I admire your optimism, even if it’s naive. But Rome calls the shots. It can’t afford the damage from dirty money.”