Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

Contest – Warren will send the tenth commenter on this post an eBook copy of his story “The Werewolf.”

Today: Warren Rochelle lives in Charlottesville, Virginia, with his husband and their little dog, Gypsy, after retiring from teaching English at the University of Mary Washington. His short fiction and poetry have been published in such journals and anthologies as Icarus, North Carolina Literary Review, Forbidden Lines, Aboriginal Science Fiction, Collective Fallout, Queer Fish 2, Empty Oaks, Quantum Fairy Tales, Migration, The Silver Gryphon, Jaelle Her Book, Colonnades, and Graffiti, as well as the Asheville Poetry Review, GW Magazine, Crucible, The Charlotte Poetry Review, and Romance and Beyond. His short story, “The Golden Boy,” was a finalist for the 2004 Spectrum Award for Short Fiction.

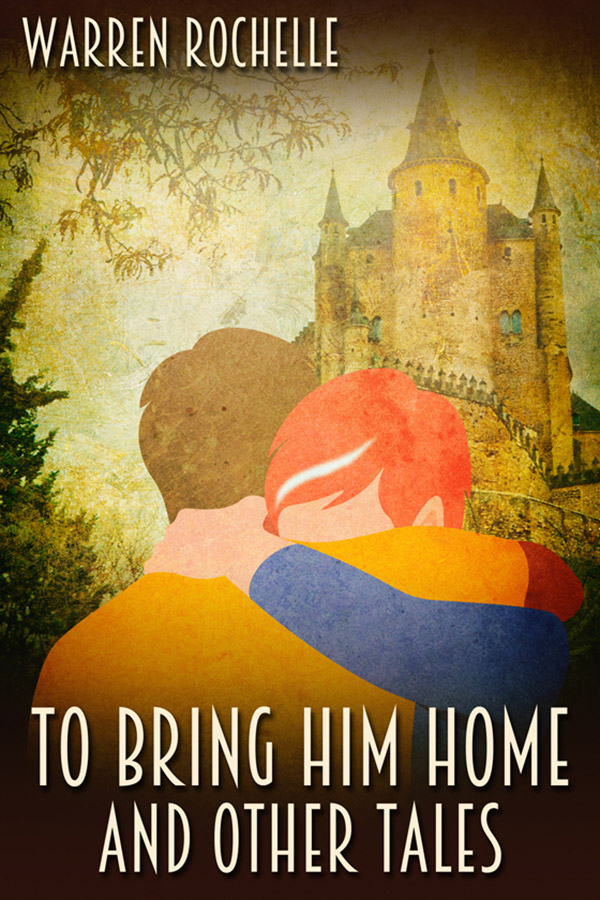

Rochelle is the author of four novels: The Wild Boy (2001), Harvest of Changelings (2007), and The Called (2010), all published by Golden Gryphon Press, and The Werewolf and His Boy, published by Samhain Publishing in September 2016. The Werewolf and His Boy was re-released from JMS Books in August 2020. His first story collection, The Wicked Stepbrother and Other Stories was published by JMS Books in September 2020. His second collection, To Bring Him Home and Other Tales, was published in September 2021, by JMS Books. A stand-alone story, “Seagulls,” was released by JMS Books in September 2021

Rochelle is also the author of a book of academic criticism, Communities of the Heart: the Rhetoric of Myth in the Fiction of Ursula K. Le Guin, published by Liverpool University Press in 2001. Other articles and book reviews on science fiction and fantasy have appeared in various journals, including Extrapolation, Foundation, North Carolina Literary Review, and the SFRA Review.

Thanks so much, Warren, for joining me!

J. Scott Coatsworth: When did you know you wanted to write, and when did you discover that you were good at it?

Warren Rochelle: When I was in third grade and read The Chronicles of Narnia for the first time. I fall in love and decided writing stories is what I wanted to do. I even wrote an awful rip-off, with a High Queen and the Plain of Fire (as in the color of the grass) and a Plain of the Moon (silver grass). Instead of centaurs, bucentaurs, humans + oxen (but I used cattle). I was quite proud of finding this species mentioned in Greek mythology and no, I didn’t know about the Venetian barges of the same name. Mercifully, I cannot find this Narnia rip-off.

When did I discover I was good at writing? This awareness was an evolutionary process. Winning a few contests growing up, getting stories published in small journals, affirmations from teachers, and finally, getting paid for a story, were all part of that process. So, to answer how long I have been writing, for almost 60 years, since I was eight. Or longer, as I drew stories all the time on the back of the used typing paper my mother brought home from her job as a secretary at Duke University. This was way before I was eight.

JSC: Have you ever taken a trip to research a story? Tell me about it.

WR: Yes, more than once. One trip was to Roanoke Island, the site of the Lost Colony. I needed to see the island and get a feel for it, so I could place a scene there in my third novel, The Called (Golden Gryphon Press, 2010). I placed a gate to Faerie off the island’s coast, and that’s how the colony got lost. The museum there had more convincing reasons.

For the same novel, I went to Cherokee, NC, to the Mountain Farm Museum, a place I’ve visited several times over the years. A shootout takes place at the Museum. I was sure I remembered just how the Museum was laid out. I was wrong.

Does a field trip to a Lowe’s Store in Richmond, VA count? A When the novel begins, my heroes in The Werewolf and His Boy are working there. They meet, fall in love, and a lot of things happen in the store. I got a map, walked the store, took notes. For the same novel, I also got my husband to drive me on an imaginary Richmond bus route, which was how the werewolf (in human form) got to work. An act of love indeed.

JSC: If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be?

WR: It will happen. Keep writing. Find your story. Tell the truth.

JSC: Are you a plotter or a pantser?

WR: Oh, definitely a plotter. Before I can start, I have to know where the story is going to end. This doesn’t have to be very specific at all. For example: at the beach, what beach, and how they got there, to be determined. Or, in the White City. Where the White City is and how they got there and why they went, are all things I will discover as the story progresses. I need to a beginning in which I can feel the flag drop, so to speak. Here, at this place, this point in time, the story moves forward, it begins. I also find myself creating up time lines of significant events to be sure the continuity works and as a part of world-building. Most of the time I prepare an outline, knowing it will change, but the outline gives me a shape and a structure within which to tell my story, and sometimes a map with which to find the story—or the part I don’t yet know.

JSC: Where do you like to write?

WR: Usually at my desk, in the study part of my bedroom. But often, at the kitchen table, everything spread out, and my husband on the couch, engaged in his projects, and our dog sleeping beside him.

JSC: How did you choose the topic for Bring Him Home?

WR: There are two answers to that question. First is the theme of gay love stories—and how? That’s because gay love stories are my stories and I want to tell them, in fantasy and science fiction. Second is the theme of home. That theme found me, or rather my best friend, Ellen, found it. Yes, she pointed out, all of the stories in this collection are love stories, but then, all of your stories are love stories. These stories are about home. She was right.

JSC: What were your goals and intentions in this book, and how well do you feel you achieved them?

WR: Two goals were to continue to explore gay retellings and to write more gay speculative fiction love stories. Another goal was to produce something beautiful, a goal I am always aspiring to achieve. I intended to continue working against such recurring themes or motifs as the gay lovers dying—or at least one of them does. The survivor, of course, is left alone, miserable, and guilty. No happily ever after of any kind allowed. I also intended, as I do in just about everything I write, to continue focusing on the intersections of the magical and the mundane.

How well have I achieved them? The goal of writing more speculative gay love stories, achieved, done. Every story in this collection is a love story, a gay love story. There are variations, such as a married couple having trouble, an orphan boy falling for a warrior who has been born and bred, and raised by a homophobic empire, a man falling for his kidnapper, and two best friends realizing they have been in love with each for years. As for gay retellings, not so much, but the title story, “To Bring Him Home,” does retell Sleeping Beauty, and re-examines the nature of the quest. “Horns, Long and Low and Dark, Far and Away” is perhaps the closest of the other stories to a retelling. The original idea was to be an answer to what would have happened if Galadriel had taken the One Ring, when Frodo and Sam were in Lothlorien. Things changed in the telling. It’s not just Galadriel, but Elrond and Gandalf who keep their rings of power as well. The result is not pretty. Yes, I know this would be out of character for Galadriel, Elrond, and Gandalf. It’s more that this idea was inspirational for The Magus, a dark trio indeed.

“Horns,” as well as “The Day After the Change,” and “Linden Grove,” all examine the intersections of the magical and mundane. Something beautiful achieved? That is a question for the reader. So, overall, yes, I did achieve my goals and I did what I intended to do, more or less. I think of achieving goals and intentions in writing are usually, for me, always in progress.

JSC: What inspired you to write this particular story? What were the challenges in bringing it to life?

WR: The answer to this question is both general and specific to the collection, to each individual story. In general, I find the inspiration for my stories—novels, novellas, and short stories—in such places as myth and traditional fairy tales, in love stories (especially gay love stories), and in the queer experience in a still-homophobic culture. I am particularly interested in exploring the idea that all fairy tales are true, and in exploring the permanent place fairy tales have in our culture. All of this led me to examine gay retellings of traditional fairy tales and to original fairy tales of my own. I am inspired by the intersections of the magical and the mundane. I also find inspiration in my own heart, and in the hearts I love. I am drawn to stories of the human condition in a queer context. Le Guin says in in her essay, “A Citizen of Mondath,” “The limits, and the great spaces of fantasy and science fiction, are precisely what my imagination needs. Outer Space, and the Inner Lands, are still, and always will be, my country” (in Language of the Night 25). In the “limits and great spaces of fantasy and science,” I also found my country, my inspiration.

The stories and novellas in this collection have their own specific inspirations. “Blue Ghosts” was inspired by two different things. Back in 2020, the folks at Queer Sci Fi issued a call for stories for the theme of fixing the world, stories to offer hope, and the possibility that things could be fixed. In the resulting anthology, aptly named, Fix the World, writers “[tackled] problems from community policing to climate change, from overpopulation to deforestation” (Coatsworth, Foreword ix). If only we had universal and unlimited power and energy, I thought. Where would it come from? How it would it change things? Hmm, in my first novel, The Wild Boy, the alien Lindauzi had unlimited power and energy. What if we got our hands on their technology? I went back to that universe and started a story. The story to be submitted for the anthology never got written, but “Blue Ghosts” did.

The second inspiration came from the blue ghosts themselves, a rare species of fireflies in the southern Appalachians. I can’t recall how I came across these beautiful creatures, but the eerie image of a blue ghost colony at night wouldn’t leave me alone. A deep-dive into some research, and blue ghosts found a home in this story.

For one more example of specific sources of inspiration for a particular story, I want to talk some about the title story, “To Bring Him Home.” Spoiler alert here, as a few details will need a closer look. This novella is an expansion and revision of a story, “The Boy on McGee Street,” published in my first collection, The Wicked Stepbrother and Other Stories (which is also a revision of a story of the same name, published in Queer Fish 2, Pink Narcissus Press, 2012). I wanted to know what happened at the end of the Wicked version. Fletcher went through the black door to rescue Sam. Did he, and if he did, how? Will these two gay lovers find happily ever after? As I wrote the expanded and re-named version I found also myself inspired again by fairy tales and the structure of fantasy, by Sleeping Beauty, by the quest.

JSC: As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

WR: A writer. Really.

JSC: Were you a voracious reader as a child?

WR: Oh, yes. At my father’s funeral, an old friend stood up in church to tell a story Daddy told him about me. I kept missing the bus. Why? Because I was so deep into reading that I failed to notice my bus had arrived at school, loaded, and left. I am still a voracious reader. I would argue a lot of writers read voraciously—as they should. A good writer is a good reader is a good writer is …

JSC: What are some day jobs that you have held? If any of them impacted your writing, share an example.

WR: Fruit fly lab student worker (I can tell you the difference between a male and a female fruit fly—you know you want to know), church janitor, babysitter, camp counselor and….

As a professional: school librarian, and a professor of English and Creative Writing.

Affected my writing? The first example that comes to mind are my four (and counting) librarian heroes.

JSC: What fantasy realm would you choose to live in and why?

WR: Narnia is always my first answer. Why? I fell in love with fantasy when I read The Chronicles as an eight-year-old. I so wanted to be able to talk to animals. I wanted to do as Eustace and Jill do in The Silver Chair and ride on the back of a centaur, and on the backs of Owls. That green and fair land has always felt like home.

JSC: How does the world end?

WR: When the clock stops, when our time is up.

JSC: Would you rather be in a room full of snakes or a room full of spiders?

WR: Well, are these poisonous snakes or spiders? In that case, the answer is neither. If non-poisonous, snakes.

JSC: What are you working on now, and what’s coming out next? Tell us about it!

WR: By the time this interview is posted, I will have turned in my novel, In Light’s Shadow: A Fairy Tale, to JMS Books. This novel has been a long time coming, as it grew out of a short story, “The Golden Boy,” published in The Silver Gryphon (Golden Gryphon Press, 2003). I have spent a good part of 2021 and 2022 on this latest version. If all goes well, the novel will be published in Fall 2022.

Next? I want to go back to the stalled sequel to The Werewolf and His Boy. I think I have finally figured out the flag-drop beginning, the one that has the energy to go forward. Another project I am contemplating is a collection of short stories or novellas exploring what happens next for my heroes in In the Light’s Shadow.

And now for Warren’s recent release: To Bring Him Home and Other Tales:

Home, a place where we belong and are safe and loved. Home, the house in which we grew up, a neighborhood, a culture, even a country. Home is a state of mind, it is a place of the heart, and in the heart.

Finding home, coming home, and bringing home the one we love is a journey, a journey that can be a dangerous adventure. For the lovers in these stories, adventures can include quests and fighting dragons and demons, past and present, physical as well as mental and emotional. Rocket launchers need to be dodged, the Wild Hunt needs to be outrun. For some of the lovers here, home has been lost, or they have been forced to leave, as is too common for LGBT+ youth.

In this collection, queer positive speculative fiction stories explore the idea of what and where home is in the lives of these lovers. Will they survive their quests, defeat their monsters? Will they find a place to call home?

Publisher | Amazon

Barnes & Noble | Kobo

Excerpt

He found his mother in her bathroom, lying on the bathmat by the tub, like a discarded hotel towel, white and crumpled. Fletcher knelt down and touched her bruised face, tenderly traced the hand prints on her skin. Cold. He then pressed his fingers against the veins in her neck. No pulse. Wishing he could cry for her, he put the same fingers under her nose. No breath, Dead. Emptied. He picked up her arm and it flopped as if boneless, She was wearing her bathrobe. He pulled it close, to hide her body.

Fletcher knew where to look, upstairs, behind the locked attic door. Through the door he could hear what he had come to call Paul’s favorite music, soft, far away, with harps and wind chimes, and what sounded like the wind, and the rain, storms. and voices singing in a strange language he had never been able to identify. The music sort of reminded him of the wind chimes on Sam’s porch. Of course.

He tried the knob. This time the door was unlocked.

“Fletcher. You’re awake. I knew you’d come up here,” his stepfather said in his cold and dark voice. He sat at a desk facing a door frame standing in the middle of the attic. Inside the door frame: darkness. Around it, Fletcher could see the rest of the attic: the shelves, the file cabinets, the odd boxes. The skylight was open, mid-day sun streamed in. Even so, the room was cold, a cold that was coming through the door, as if blown by some faraway wind. Paul’s black staff leaned against the door frame. He closed a little carved box on his desk and the music stopped.

“What did you do with Sam? Where is he? Where are his parents?” Fletcher asked, shivering and hugging himself against the cold.

“Where they belong,” Paul said, leaning back in his chair. “The dreams have escaped for millennia — even before Her Majesty came to power — into human minds. Fairy tales, myths, story upon story. A few times, the different peoples and creatures slipped through — what was it your hero said? — ‘there were many chinks or chasms between worlds in old times’? — yes, I’ve read all those stories, too; they were useful to me. That was before Her Majesty. So, there are people like you and your mother, fey-touched, gifted with Sight that lets you see through glamour. Very useful to people like me.”

Fletcher swallowed the scream in his throat, knowing he had to listen, to understand, not to let this man get to him, break him into tears. “Where is Sam? What kind of a person are you?”

“I told you: There. You can call it Narnia if you like, or what did Tolkien call it? Never mind. The Celts came up with many other names, such as Tir n’Og, the Blessed Isles. Words and sounds can be dreamt, too; echoes can linger. She can’t stop the dreams of what once was, of once upon a time — slow them down, but not stop them. But Her Majesty can and must stop those who escape her winter,” Paul said, as he sorted what looked like rolls of parchment, stuffing some back into tubes, into different parts of his desk. “I am a bounty hunter, a tracker, and you, my dear Fletcher, and your mother, are my canaries.”

My dreams. I dreamed of the neighbor, I dreamed of Sam. Now I know where his music comes from.

“They hadn’t planned on Sam falling in love and having sex quite just yet, which shattered the weak child’s glamour — and I smelled him on you, his magic,” Paul said, his words dripping disdain and scorn.

“Mama’s dead.”

Paul shrugged and Fletcher hated him for it. “I needed her energy to open the gate — I was running a little low. A few days from now, no problem. You want him back?”

Fletcher slowly and carefully nodded his head.

“You think you’re in love. Fletcher! What do you know about love — who have you ever loved or who’s loved you? And when he asked for you, at the moment of peril, you pulled back. Don’t be a fool: you’re not in love.”

“My father loved me; I loved him. My mother — before you used her for food. Sam loves me.”

“Then go get him. Into Faerie. No happy elves, no dancing fauns, no chatty mice, no heroes with magic swords. No performing Lion, just Her Majesty’s winter. No English children. Your boyfriend’s there, Fletcher. Or you could stay here and help me — starting with finding that sanctuary. Do you know how old I am? Her Majesty rewards her faithful: I am two hundred and thirteen of your years old. I have anything I want.”

I want Sam.