Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

Rick R. Reed is an award-winning and bestselling author of more than fifty works of published fiction. He is a Lambda Literary Award finalist. Entertainment Weekly has described his work as “heartrending and sensitive.” Lambda Literary has called him: “A writer that doesn’t disappoint…” Rick lives in Palm Springs, CA, with his husband, Bruce, and their rescue dogs, Kodi and Joaquin

Thanks so much, Rick, for joining me!

J. Scott Coatsworth: When did you know you wanted to write, and when did you discover that you were good at it?

Rick R. Reed: I’ve been writing since I was knee-high to a grasshopper. Or, to put it in less cliché terms: I wrote my first short story around age 6, my first play in 4th grade, and my first novella, about a kidnapping, in 5th grade, which I read aloud to my class in installments. They were enthralled and that was a turning point for me, a shy kid, to realize I could entertain and make people think with my words. I also got verification of my ability in 7th grade when my English teacher was floored by my short stories and encouraged me. Also, in 10th grade I wrote a story about the conflict in Belfast, Ireland. I can still see the A+++++ the teacher put at the top of the story.

But I suppose when I really felt validated was when I got my first literary agent in the early 1990s and she sold two novels (Obsessed and Penance) over the next couple years to Dell in New York.

JSC: How would you describe your writing style/genre?

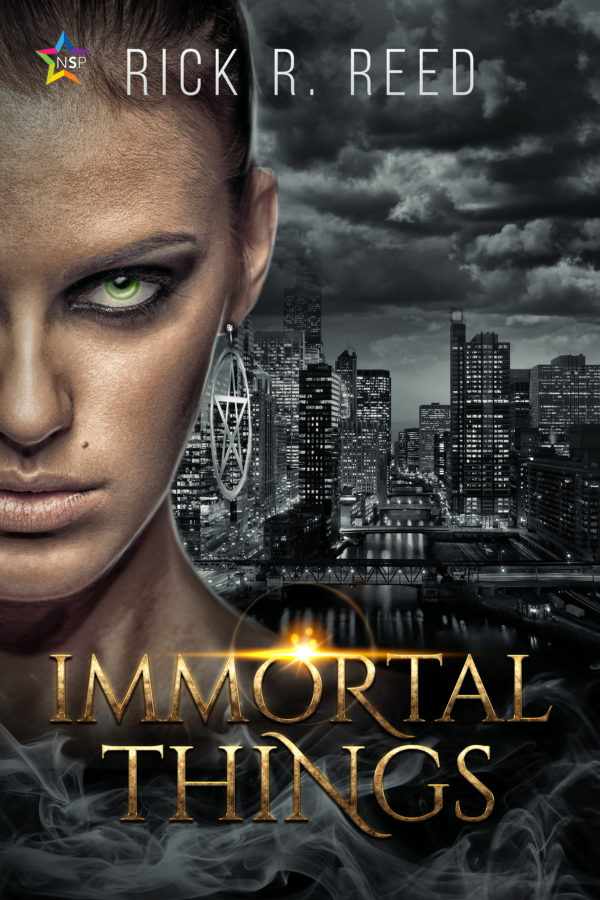

RRR: I like to write about people whom we can identify with (common hopes and dreams, universal struggles and joys) and put them into extraordinary situations. I flout convention when it comes to labels. My work often incorporates elements of horror, psychological suspense, romance, and other genres…sometimes all in one book (see Dinner at the Blue Moon Café, which marries the paranormal and romance with werewolves or Immortal Things, which is a mash-up of a great love story with vampires). I do write, though, some stories that lend themselves to easy categorization and most of these are either romance, horror, or thriller.

JSC: What do you do when you get writer’s block?

RRR: I have never believed in it. And you know what? I have never suffered from it. I think the cure for so-called “writer’s block” is disciplining yourself and getting your butt in a seat in front of a keyboard or, if you’re old school, pen and paper. We need to be open to receive. If we’re moaning about writer’s block and not opening ourselves up to receiving ideas, then of course we’ll be blocked. Sorry, it’s too easy of an out.

JSC: Do you use a pseudonym? If so, why? If not, why not?

RRR: No. I guess I use up too much imagination creating characters, places, and how they fit into a story. I have no real reason to use a fake name.

JSC: If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be?

RRR: You can’t underestimate the value or reading a lot and writing a lot.

JSC: Do you ever base your characters on real people? If so, what are the pitfalls you’ve run into doing so?

RRR: I would say that many of my characters are different aspects of myself. Sometimes, as in a book like Caregiver, I based a main character on an unforgettable person I loved and lost. For me, no pitfalls. It’s easier for me to write what I know, even if that knowledge is put into a situation I’m unfamiliar with.

JSC: How long do you write each day?

RRR: As long as it takes to get about one thousand words down on my work-in-progress. That time also involves re-reading and editing the previous day’s work and more. All told, I suppose I spend my mornings (2-4 hours) writing and editing.

JSC: Do you read your book reviews? How do you deal with bad or good ones?

RRR: Yes. And, for the most part, am pleased with what I read. Of course, as anyone who’s been in this business as long as I have will tell you, I’ve run across some constructive criticism that’s helpful and, unfortunately, a lot of cruelty steeped in anger that I didn’t write the book the reader wanted.

JSC: How long on average does it take you to write a book?

RRR: Usually about three to four months. When I’m working, I’m working!

JSC: Are there underrepresented groups or ideas featured if your book? If so, discuss them.

RRR: Yes, I proudly consider myself an #ownvoices writer, which means I’m part of a marginalized community (LGBTQ) and I write about things I’ve encountered as a gay man in my life. I have dealt with AIDS, substance abuse, hate crimes, same-sex marriage, online relationships, and more in my work.

JSC: How did you choose the topic for Immortal Things?

RRR: In Immortal Things, I use vampirism as a metaphor for the thirst for immortality that’s behind artistic endeavor.

JSC: Tell us something we don’t know about your heroes. What makes them tick?

RRR: My vampires are sexy, tortured and often brutal. They have a passion for art, yet their sacrifice in becoming immortal means that they’ve given up their ability to create. This dilemma is at the heart of Immortal things.

JSC: Who did your cover, and what was the design process like?

RRR: Nastasha Snow, at Ninestar Press. She’s an amazing cover artist and I need only give her a vague suggestion and she can run with it—creating a cover that’s not only gorgeous, but marketable.

JSC: Who has been your favorite character to write and why?

RRR: Probably Bobby in Raining Men because he was so hated and hateful. It was quite a reward for me to know I succeeded in taking someone so reprehensible and, through his journey, making him a character readers would not only root for, but also come to care deeply about.

JSC: As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

RRR: A writer. Boring I know, but it’s all I ever wanted to do.

JSC: If you had the opportunity to live one year of your life over again, which year would you choose, and why?

RRR: No thank you. Life is a forward-moving train. There have been years of great delight and years of great sorrow. They’re all paths on my journey.

JSC: Tell me one thing hardly anyone knows about you.

RRR: I adore Judge Judy.

JSC: Tell me about a unique or quirky habit of yours.

RRR: Besides picking my nose? I guess I’d say having to always start a Kindle book at the cover.

JSC: Were you a voracious reader as a child?

RRR: Yes.

JSC: What pets are currently on your keyboard, and what are their names? Pictures?

RRR: There are no pets on my keyboard. I have two rescue dogs, Kodi and Joaquin, whom I adore. They often snooze behind me while I work.

JSC: What other artistic pursuits (it any) do you indulge in apart from writing?

RRR: I love to cook. It relaxes me and I love the improvisation aspect.

JSC: What are some day jobs that you have held? If any of them impacted your writing, share an example.

RRR: I’ve always been a writer in one form or another. When I worked in corporate, I did stints as a copywriter at an ad agency in Chicago, a marketing writer for a large professional healthcare association, and a communications consultant for a company that worked on government healthcare initiatives.

JSC: How does the world end?

RRR: With a whimper.

JSC: Star Trek or Star Wars? Why?

RRR: Neither. Yuck.

JSC: What meds are you supposed to be taking?

RRR: I’ll defer to HIPAA rules on that one.

JSC: What’s your drink of choice?

RRR: Usually iced tea or coffee.

JSC: What’s in your fridge right now?

RRR: Too much stuff to list.

JSC: What food(s) fuel your writing?

RRR: Breakfast foods because I’m a morning person and write in the mornings pretty exclusively.

JSC: What are you working on now, and what’s coming out next? Tell us about it!

RRR: I have a romantic suspense novel, TOXIC, coming out early next year from Ninestar Press. Here’s the blurb:

Connor Ryman thought he had it all—a successful career as a mystery novelist, a condo with stunning views of Seattle’s Lake Union, a supportive and long-term partner, Steve, and a loving daughter, Miranda, who was following in her father’s creative footsteps.

It all went bad when Steve left the family suddenly. Jilted and heartbroken, Connor begins to search for love online. So long off the market, he enlists his daughter’s help in crafting a dating profile.

His prayers are answered when Trey Goodall, smart and handsome, answers his ad. He’s witty, urbane, a wealthy attorney, and his sex appeal is off the charts. But he’s a liar, a monster under a pretty mask. Miranda sees through the red flags and senses something very wrong beneath the façade.

Can she convince her father to save himself before it’s too late? Or will Trey, a master manipulator with a very tainted history, play upon Connor’s innocence to ensnare him in a web of deceit, intrigue, and, ultimately, murder?

And now for Rick’s new book: Immortal Things:

By day, Elise draws and paints, spilling out the horrific visions of her tortured mind. By night, she walks the streets, selling her body to the highest bidder.

And then they come into her life: a trio of impossibly beautiful vampires: Terence, Maria, and Edward. When they encounter Elise, they set an explosive triangle in motion

Terence wants to drain her blood. Maria wants Elise . . . as lover and partner through eternity. And Edward, the most recently converted, wants to prevent her from making the same mistake he made as a young abstract expressionist artist in 1950s Greenwich Village: sacrificing his artistic vision for immortal life. He is the only one of them still human enough to realize what an unholy trade this is.

Immortal Things will grip you in a vise of suspense that won’t let go until the very last moment…when a shocking turn of events changes everything and demonstrates—truly—what love and sacrifice are all about.

Amazon | Universal Buy Link

Excerpt

No one can hear the screams, the cries for mercy, and the shrieks of agony. It is as though the house is alive and it clamps down in reaction to the turmoil going on inside. One would never guess from its calm exterior that blood drips from its walls and those unlucky enough to enter have a good chance never to emerge again.

This house appears to be empty. Dignified. Crumbling testimony to the wealth that once existed on Chicago’s Far North Side. It sits like a boulder on a corner, empty-eye-socket windows facing Sheridan Road and beyond it, the expanse of Lake Michigan. The lake is dark now; white-tipped waves crash against the shoreline, breaking at the boulders, a crescent moon bisected and wobbling on its black and churning waters. The house has borne witness to these waters, moody and changeable, always fickle, for more than a hundred years.

The house is fashioned from white brick, yellowed and dirty. Nothing grows in the yard, save for a few straggling weeds that refuse to give in to the barren soil.

The house is dead.

And so are its inhabitants.

*****

The dead are inside and reveal a surprising likeness to living creatures. They can move and speak just like the rest of us. They have wants and needs. They go about fulfilling these wants and needs with the same kind of intensity and purpose as the rest of the world. One could even say they have jobs, even if their occupations would be deemed illegal and certainly immoral by almost everyone.

But look beyond these superficial similarities and you’ll feel chilled. Touch their flesh and it’s cold. Lay your head at their breasts and hear…nothing. Look into their eyes and find yourself reflected back in a black void that you just know, if you linger too long in its embrace, you’ll be sucked in and it will be all over for you. Grab one of their cold wrists and feel stone, marble to be exact.

There is no pulse.

But tonight, they are a merry band of three. Like the living, they are filled with anticipation. An evening out awaits them. They will, like so many others getting ready for a night on the town, meet others, exchange knowing glances and a mating dance of words. They will sup, but not on the gourmet offerings of the city.

Most houses borne of this period contain many rooms, perhaps more than necessary. Whoever designed this house had the presence of mind to create wide-open spaces, breathing room. Enter the double front doors and you come directly into the living room. Or is it a drawing room? A great room? No matter. What you do not enter is a vestibule or a foyer as other houses of this period would contain. The walls are parchment colored, but right now, that color is indiscernible to the human eye, lit as they are by dozens of flickering candles. Water stains mar the walls and give to them a trompe l’oeil elegance, a look of almost deliberate aging. The floors are dark, their hardwood planks, tongue and groove, blackened by the lack of light and dust accumulated over many years. Along one wall is a fieldstone fireplace, its mantel tall as a man, its hearth cold and empty.

There is no furniture in this huge room. No chairs. No tables. No bookcases or desks. No divans or chaise lounges.

What does occupy the room, other than these three lifeless, yet curiously beautiful souls, is art. Paintings of every period lean against the wall and hang from their crumbling surfaces. Here is one after the style of Rubens, there another that looks pre-Raphaelite, here a Picasso…Jackson Pollock…Monet…Keith Haring…Willem de Kooning…Mark Rothko…Barnett Newman…plus the works of a legion of unknown artists, in every style and medium imaginable. The walls are crowded with it. The room is a gallery assembled by someone with vast resources, but tastes that go beyond eclectic. The only common theme running through these works is that all are unique. There is a respect for form, for color, for technique. Most of all, there is a certain indefinable quality that manages to capture the human spirit in its delicacy, in its discontent, in its hunger.

Perhaps it’s the hunger that appeals to them.

And the floor is a cocktail party of human sculptures. Men and women carved from marble, granite, and alabaster, cast in bronze. There are later figures cast from polymers, smooth acrylic, welded metals.

It is eerie—this empty house that has become museum or mausoleum.

Or both.

But art is what the dead crave. It sustains them—that and something else—something warmer and more vibrant, but they are too genteel to admit to such hungers. Like animals, they simply feed when they are hungry and discuss it as little as possible.

The walls also contain long leaded-glass windows, through which, appropriately enough, a full moon sends its pale rays, distorted and laying upon the darkened wood like silver. The leaded glass has become opaque, obscured by layers of dust, grime, and accumulated smoke.

And we can see the creatures now, gathering. Listen: and hear nothing save for the creaking of ancient floorboards.

First, let us consider Terence, broad shoulders cloaked in a pewter, latex zippered vest open just enough to display the cleft between smooth and defined pecs, tight leather jeans, and biker boots. Blond hair frames his face in leonine splendor: thick, straight, and shining, it flows to just below his shoulders. Glint of silver on both ears, studs moving like an iridescent slug upward. Terence is the second oldest of the three. His skin, like the others, has the look and feel of alabaster. Dark eyes burn from within this whiteness and present a startling contrast. Terence is a study in symmetry: his wide-set eyes match each other perfectly, his aquiline nose bisects dramatic cheekbones, and his full lips speak volumes about sensuality and lust. Stare into Terence’s eyes and gain a glimpse—quick, like a jump cut in a movie—of cobblestone streets, horse-drawn carriages, and the grime and elegance that was London in the late 1800s. Shake your head and the image disperses and you are left thinking it’s only your imagination conjuring up these images. After all, what does this post-punk Adonis have to do with the British Empire in the time of Oscar Wilde? Besides, Terence’s smile will have you thinking only of the present. And the present is what Terence lives for—the pleasure he can find, the communion of flesh and blood, seemingly so religious and yet sent from hell. He throws back his head and does a runway model turn, for the benefit of his companion, Edward, who rolls his eyes and snickers. “Don’t look to me to be one of your adoring minions.”

Let’s shift our focus to Edward. Edward is musculature in miniature, stubbled face and a shaved pate. Leather vest, black cargo pants tucked into construction worker boots, no jewelry save for the inverted cross glinting gold between shaved and defined pecs. On his bicep, a tattooed band: marijuana leaves repeated over and over, rimmed with a thick black line. Edward’s look would be comfortable in the leather bars along Halsted Street, and he is the only one of the three who prefers the embraces of men. He is relatively young, a newcomer to this scene of death and the greedy stealing of life. Watch him carefully and you will detect a hint of uncertainty in his handsome, rugged features. Melancholy haunts his dark eyes, which, unlike Terence’s, are not symmetrical: the left is a little smaller than the right and crinkles more when he laughs, which is seldom. Curiously, though, it is Edward’s features that look most human…because it’s humanity that lacks perfection and Edward hasn’t been of this undead world long enough to adopt its slick veneer of beauty that’s too perfect to be real or wholesome. Look into Edward’s eyes and you’ll see a beatnik Greenwich Village, a more personal vision: an artist’s studio which is nothing more than a cramped room with bad light with canvases he worked on night and day, brilliant blends of color and construction for which Edward had no name, but one day would be called abstract expressionism.

Shake your head, and—as with Terence—these images disperse. There’s nothing there, save for this macho gay clone boy with eyes that still manage to sparkle, in spite of the thin veneer of sadness and remorse deep within them.

And last comes Maria, on silent cat feet, moving down the stairs. A whisper of satin, the color of coagulating blood: rust and dying roses, corseted at the waist with black leather. Black hair falls to her shoulders, straight, each strand perfect, sometimes flickering red from the candles’ luminance. Dark eyes and full crimson lips. Maria stands over six feet, and her body, even beneath the dress, is a study in strength: muscles taut, defined, like a man save for the fact that the muscles speak a hypnotic feminine language: sinew locked with flesh in elegance and grace. “Feline” would not be going too far were one to describe her. There is the same grace, the same frightening coiled-up power, perfect for the hunt, perfect for surprising and making quick work of her prey.

She pauses, turning slowly in front of the men, her men, waiting for an appraisal. And, unlike Terence, this move does not seem vain, but more her due.

The men applaud softly and Maria stops, dark eyes boring into theirs. They do not see the watery streets of Venice, but you would, if you dared to engage her gaze for long. Dark canals and mossy mildew-stained walls, crumbling stairs at which black water laps, an open window through which one hears an aria. Smell the mildew and the damp.

The three take seats on the dusty floor, bring out mind-altering paraphernalia.

Terence, first: “Whom will we lure tonight?”

And Edward, eyes cast downward, the candle flames reflected off his bald and shining pate, sighs.

It is Maria who touches him, her hand a whisper, but with the tightness of a claw against his shoulder, forcing him to look up into her eyes. “I know it’s hard. But eventually you’ll come to understand, to be like Terence and enjoy what is natural.”

Edward laughs, but there is no mirth in it. “Natural? You call what we do natural?”

“We are God’s creatures, just like the ones we prey upon. Just as an owl preys upon a mouse. We have needs and we do what we must to satisfy them—or else we die.”

“We’re already dead,” Edward says.

Maria picks up a glass cylinder and looks at it critically for a moment. “Legend looks at us that way. That much is true.” At the top of the cylinder is a small bowl, which Maria stuffs with sticky, green bud. The smell of marijuana is redolent in the air, mixing with the burning wax of the candles. “But I prefer to think of us as another species. A different kind of animal.”

Edward stares at the silver light coming in through the long leaded-glass windows. It has been more than fifty years since he first met Terence in a tiny basement bar in Greenwich Village. Fifty years since he transformed himself into this new kind of animal Maria is now trying to make him think he is, to excuse their killing, the mayhem they wreak wherever they go. The heartbreak and the bloodshed, the latter so delicious, and so damning. Will he ever become callous enough to view what they do and what they are, like Maria? Will he ever be able to look at one of their victims, convulsing before them on a grimy floor, surrendering to death, and see them as merely sustenance? He’ll never believe it.

The most curious thing about his transformation is this: time has taken on completely different dimensions.

Five decades have passed like five days. It makes eternity easier to bear, he supposes.

“If that’s what gets you through the night, Maria, fine. And as for being like Terence one day, well, that’s a hell I hope to never visit.”

His last comment elicits a snort from Terence, who seems to either find everything humorous or everything sexy. He lives for pleasure. Sometimes, Edward wishes he could be like him. Terence has no conscience. It would be easier to be so ignorant.

“Here.” Maria hands him the glass cylinder, the thing that in a head shop would be called a Steamroller, and Edward fishes in his vest pocket for a disposable lighter. He fires it up and holds it to the little ashen bowl topping the cylinder, watching as it grows orange and holding his hand over the open end of the tube. It fills with smoke. When Edward removes his hand, the blue-gray smoke rolls toward him, into his open mouth, and he longs for the oblivion he knows it will bring. He holds the smoke deep in his lungs and then exhales. It doesn’t take much of this stuff to change his mood, to make him forget, and for that, he’s grateful.

He hands the cylinder to Terence, who locks his hand over his and stares into his eyes. “You always were so beautiful,” he whispers.

“You always were such a liar.”

And the merry band of three becomes silent and a little less merry. They know the truth: Terence is a liar, and had it not been for his charm and deceptions, Edward would not be with them tonight.

No, Edward would not be with them. He would be a man in his seventies by now, either a bum or a respected abstract expressionist painter; in the movie of his life, someone short but muscular would play him; the title of this film would not be Pollock, but Tanguy. Instead, Edward was no longer an artist, no longer a human being really. No, he is now a creature who has made stealth and superhuman attunement his artistic expression. He thinks, with a dark snort, that all he draws now is blood.

Maria’s cold, satin flesh takes hold of his forearm; the slight pressure of her nails: the gentle touch of a bird of prey’s talons. Even with his own kind, Edward thinks, one can’t be too careful.

She knows he is not attuned to the night, but is depressed and resigned to the hunt. He has never fully realized the joy of taking sustenance. Maria stares into his black irises with her own pitch orbs, and smiles. She licks her lips and raises her nose to sniff. “Mmm. Can’t you smell them, Edward? The sharp, hot tang?” She closes her eyes in a kind of rapture, breathing in deeply. The smell of people wafts through the hot summer air, as much a background as the bleating horns, exhausts, and squealing brakes from the cars on Sheridan Road.

Edward allows Maria to lead him to the front door. Puncture or perish is the joke he whispered to himself.

Terence waits at the curb, his big Harley churning and revving. He grins and one can see, even from yards away, Terence’s eyes twinkling with anticipation.

Edward thinks as he descends the wide flight of stairs, Maria clutching his arm, that Terence is the luckiest of the three because he feels no remorse.

He has no heart.