Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

Today: Richard Thomas is the award-winning author of nine books: four novels—Incarnate (Podium), Disintegration and Breaker (Penguin Random House Alibi), and Transubstantiate (Otherworld Publications); four short story collections—Spontaneous Human Combustion (Turner Publishing—Bram Stoker finalist), Tribulations (Cemetery Dance), Staring Into the Abyss (Kraken Press), and Herniated Roots (Snubnose Press); as well as one novella of The Soul Standard (Dzanc Books). His over 175 stories in print include The Best Horror of the Year (Volume Eleven), Cemetery Dance (twice),Behold!: Oddities, Curiosities and Undefinable Wonders (Bram Stoker Award winner), The Hideous Book of Hidden Horrors (Shirley Jackson Award winner), Lightspeed, PANK, storySouth, Gargoyle, Weird Fiction Review, Midwestern Gothic, Shallow Creek, The Seven Deadliest, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, Qualia Nous (#1&2), Chiral Mad (#2-4), PRISMS, Pantheon, and Shivers VI. He has won contests at ChiZine and One Buck Horror, has received five Pushcart Prize nominations, and has been long-listed for Best Horror of the Year seven times. He has also edited five anthologies: The Best of Gamut (House of Gamut), The New Black and Exigencies (Dark House Press), The Lineup: 20 Provocative Women Writers (Black Lawrence Press) and Burnt Tongues (Medallion Press) with Chuck Palahniuk. He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker (twice), Shirley Jackson, Thriller, and Audie awards. He is currently the Editor-in-Chief at Gamut and previously held the same title at Dark House Press. His agent is Paula Munier at Talcott Notch. For more information visit www.whatdoesnotkillme.com.

Thanks so much, Richard, for joining me!

J. Scott Coatsworth: When did you know you wanted to write, and when did you discover that you were good at it?

Richard Thomas: I’ve always loved reading and writing, going back to grade school. I started reading Stephen King in high school, the same year I saw a guy parachute to his death at the base of the St. Louis Arch—which may have been part of the reason that I started writing horror. I got good grades in all of my English and Creative Writing classes, but it wasn’t until I took a class with Craig Clevenger at the age of 40, and then published a story (“Stillness”) with Cemetery Dance, in Shivers VI (alongside Stephen King and Peter Straub) that I felt like maybe this could be a career for me. Fifteen years later, here I am—writer, editor, teacher, and publisher.

JSC: How would you describe your writing style/genre?

RT: I came up writing neo-noir, transgressive thrillers—realism that was dark, visceral, and intense. Years later I’ve shifted more into new-weird, speculative fiction. My MFA infused my writing with literary aspirations, and I’ve always been a maximalist—heavy with setting and sensory details. I think Chuck Palahniuk said it really well with a blurb for my last collection of stories, Spontaneous Human Combustion (a Bram Stoker finalist) when he said: “In range alone Richard Thomas is boundless. He is Lovecraft. He is Bradbury. He is VanderMeer.” I definitely lean into the weird and uncanny, sometimes cosmic horror, with roots in horror. I try to write body, mind, and soul—entertaining fiction that makes you turn the pages; emotional depth that gets a reaction; and intellectual stimulation that makes you pause and think.

JSC: What’s the weirdest thing you’ve ever done in the name of research?

RT: LOL the first thing that comes to mind is when I was writing my second novel, Disintegration. There was a scene where the unnamed protagonist is losing his mind, and misses his cat, and so he shoves a handful of cat food into his mouth and eats it. So I did the same thing. Not wet food, I’m not a monster, but the dry food—wow. Even the chicken tasted like fish, salty and gritty. Blech.

JSC: If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be?

RT: Quit drinking and start writing. I’ve been sober 21 years now, but man do I feel like I wasted 20 years not writing, when I could have been honing my craft, building up my networks, and publishing a range of stories and novels. I got caught up in the Hemingway concept of being a man, and an author—drink hard, play hard, have sex, travel, and then bang out a story on your typewriter. What a bunch of crap. Oh well, hindsight is 20/20 right?

JSC: How long on average does it take you to write a book?

RT: Kind of a tricky question. I might take months, or even years to do research before I sit down and write, but then it might only take a month. I wrote half of Disintegration in one week (40k), all of Breaker in 25 days (75k), and most of Incarnate (52k) in two weeks (78k total). For Incarnate I spent two years watching movies like The Thing, television shows like The Terror, as well as YouTube videos on Alaska and the Arctic, documentaries, etc. As well as reading many different stories and novels set in these environments, fiction and nonfiction. When I’m writing a novel, I like to stay focused, to put on that skin suit, to become a “method writer” and channel the visions and images that come to me, organically, reacting as the protagonist would react. I’m a pantser, not a plotter, so while I have an outline, I don’t plot out everything in advance.

JSC: What is the most heartfelt thing a reader has said to you?

RT: I got a message on Facebook from a reader who had been thinking about killing himself, and he read one of my stories, and it gave him hope, a reason to live, and so he thanked me for putting the work out there, for taking the chances that I did, because he felt less alone. I had a reviewer reach out to express thanks for Incarnate, as it helped them to deal with the passing of their father, in a very cathartic way, crying when they needed to, but coming out of it feeling okay, stronger, like they could manage the grief. Those kind of messages really resonate with me, and make it all worth while.

JSC: What tools do you feel are must-haves for writers?

RT: You can be born a natural storyteller—have a love of reading, film, television—and have the imagination and vision, and those gifts will benefit you, but if you don’t study, and understand the mechanics, your stories won’t work. Likewise, you can be born less talented, but apply yourself, study and work hard, and be just as successful, IMO. I use Freytag as the structure for my stories, and it’s what I teach. Narrative hook, inciting incident, exposition and world building, internal and external conflicts, rising tension, that leads to a climax with resolution and change, as well as denouement. If something is missing, it’s probably one of those elements. You have to put in your 10,000 hours, you have to hone your craft. It takes time. I tell my student to give themselves THREE YEARS to study, write, find their voice, edit, and grow. Those that take my core classes—Short Story Mechanics followed by Contemporary Dark Fiction and then my Advanced Creative Writing Workshop—do really well. It’s like going from high school to college to MFA in the span of three classes. And if they’ve done well, I encourage them to write a novel with me, in my novel-in-a year class. Stephen King said, “If you want to be a writer you must do two things—you must read, and you must write.” I agree, 100%.

JSC: What was the most valuable piece of advice you’ve had from an editor?

RT: Sounds cliché, but write what you know. Let me explain that a bit. It doesn’t mean you can only write about being a teacher, living in Ohio, and being a white man. I tell my students to find their voice. Where do they come from, what are their favorite authors, books, stories, movies, television shows? What authors have had the most influence on them, and what genres do you ingest, and write? And then, use everything you have—your jobs, your city, your relationships, your sex life, your culture, your people, your myths and legends, your experiences. Use that as a jumping off point, and then make it different, make it your own. That’s why a werewolf story by Stephen Graham Jones is different than one by Benjamin Percy, why new-weird by Jeff VanderMeer is different than China Mieville. Is why an Anne Rice vampire story is different than one by Catriona Ward.

JSC: How did you choose the topic for this book?

RT: I always tell my students that for a novel, especially, you must be fascinated with the story, feel you have the authority to write it, and the voice to lean into those genres. Chuck Palahniuk says, “Teach me something, make me laugh, and then break my heart.” I love that, but usually it’s “scare or unsettle me” instead of “make my laugh.” So for Incarnate it started with the idea of emotions manifesting into a physical form, partly inspired by Micaela Morrissette’s story, “The Familiars,” where the creature is a manifestation of grief. As a maximalist I was also fascinated with Barrow, Alaska (now called Utqiagvik) where there is 60-90 days of darkness—and what might thrive in that environment. Add to that a sin eater, something that has always intrigued me, and moments to tap into my love of food, and you have a novel that grabbed and held my attention for 78,000 words. I also wanted to write a horror novel that had hope in it (“hopepunk”) and this three act structure, with three POVs, really made that possible.

JSC: What was the weirdest thing you had to Google for your story?

RT: Mostly it was just trying to get the environment right. I did so much research, and in fact, hired an “Arctic expert” in Repo Kempt to help me get it right. I had to not only avoid overusing words like snow, cold, and ice, but do research on customs, work, food, flora and fauna. I couldn’t just say “pine tree” I had to find ten different variations, and at what altitude, and how did nature shift and change. What happens if you go outside naked, how quickly will you die? Why do people leave a block of pure glacier ice on your porch, as a new resident, with an ice pick imbedded in it? Do they really hunt whales, and how do they kill it, divide it up, distribute it to the community, and use all of the body part? Fascinating stuff for sure.

JSC: What are you working on now, and what’s coming out next? Tell us about it!

RT: Mostly I’m editing and teaching, but I’m working on a new story for Three-Lobed Burning Eye. Been contemplating writing my first werewolf story, but I want to do something radically different, and so I have to really study all of the rules, legends, and lore before I can push away from them, and yet keep that core concept of the shapeshifter. I’ve also been doing research on my next novel, about vibrations, kind of a new age horror story, tapping into holistic medicine, as well as the idea that we are always surrounded by the uncanny, weird, and supernatural—ghosts, spirits, angels, demons, monsters, aliens—you name it.

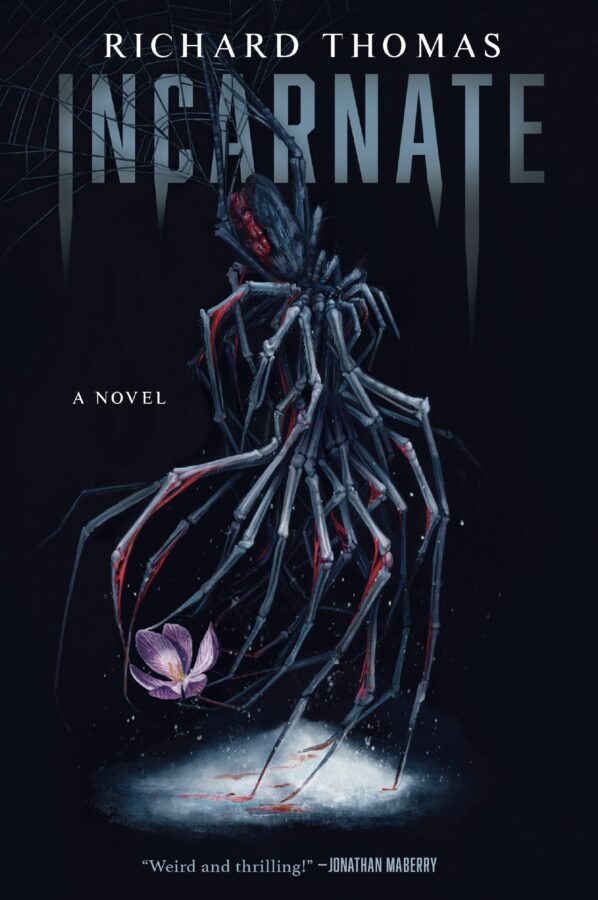

And now for Richard’s new book: Incarnate:

In a frozen tundra, one man fights for redemption as monstrous creatures ravage a community already struggling to survive.

Sebastian Pana is a “sin-eater,” a shaman-like figure who can absolve the dead of their transgressions before they move on to the afterlife. But when Sebastian’s small arctic town is invaded by hideous, otherworldly beasts, he must wage battle with them the only way he knows how: by unleashing the power of sin itself.

From an author who has been compared to Lovecraft, Bradbury, and Gaiman, Incarnate is a masterpiece of contemporary arctic horror—both an epic confrontation between the forces of good and evil and a profoundly redemptive tale about our eternal quest for forgiveness.

Amazon

Excerpt

PROLOGUE

As I stare across the never-ending whiteness that is my arctic prison, I realize that while I seek isolation at times, the work requires me to interact with the locals—we each have something that the other party needs. And out here in the frigid wilderness, the night creeps in, expanding across several months, making my life, and duty, that much more difficult. I’m not getting any younger, and the cabin I live in, while ringed with several layers of protection, is not going to keep me safe from my work.

Not forever.

I have to seek out my neighbors, this tricky relationship we have—my way of helping them to cross over, them giving me what I need to keep the shadows at bay. To the naked eye, I am an elderly man, at the edge of town, constantly chopping wood, planting strange bushes and flowers when the ground isn’t frozen, a smile and a wave as hunters pass by with their kill. Inside this ancient flesh, I’m something else entirely. Soon, the village will be buried, the passes closed by chest-high snowdrifts, roads erased, nothing entering, and no way out as well. It’s a good time to regroup, to heal, and prepare for the long night, as the woods will come calling soon enough.

My name is Sebastian Pana, and I’m growing tired, but there is much to do as winter approaches, never truly going away, always lurking, my life held in my shaky, freezing hands every time I step outside. There are so many ways to die here—the cold, the wet, the animals hungry at the edge of your vision, the isolation, starvation, drink, the traditions, and loneliness as well. I have few friends, and that is on purpose, but I am still human, for the most part. I long for companionship, as much as I seek out warmth, and enveloping peace. When I push out into the endless void, it is with a bright light, on the end of a long, sharp stick.

The veil is weakening, and they’re pushing through. I fear it won’t be long now.

ACT ONE: THE SIN-EATER

CHAPTER ONE: Arriving

The darkness is expanding—sixty days of night looming on the horizon—so I step out onto my porch and take a deep breath, the cold air burning my nostrils and making my lungs ache. There is so much to do, so much pain to repurpose into the void. I rub my hands together to warm them, already dressed in layers—long thermal underwear over boxers, two pairs of wool socks—with more to come. The morning is brisk, hoarfrost sparkling across the snow-covered ground, but I know I can’t stand here for long. I inhale again—juniper, salt, a whiff of fish, my own musk—and take in my humble abode, knowing that the season is upon us, preparing for what will come. It is both invigorating and daunting at the same time.

My neighbors give me a wide berth, the odd man on the hill, at the foot of the mountain. I am far enough away for them to feel safe, but close enough that they can walk to me with their offerings, and requests. I’ve been here for years, but not as long as some say. When they pass my cabin, they talk of the boy that used to live here, and then the man who took his place, now an elderly curmudgeon holding down the fort. If they did the math, it wouldn’t add up. They boy, the father, the grandfather—we are one in the same. Not three separate individuals, but one soul, aging at a rapid pace. It all comes at a price, this calling. The trek I took north, away from friends and family, all assuming me dead now, this dot on a map my destination, the tear in reality my post.

When I got here, there was little work, the village struggling, most residents hunting and fishing to survive, sometimes working with local scientists doing research, sometimes traveling to larger cities for factory jobs, or down to the water—the cannery, and various boats providing sustenance. Some make a living guiding tourists in search of big game. We all live off the land in one way or another, taking so much, and giving back so little.

There were empty apartments, dilapidated houses, and abandoned warehouses everywhere—so many places to curl up, freeze, and die. This was not my first rodeo, other places across the land having similar pockets of darkness and vulnerability. And for a while I’d toil there until the wounds healed, and my work was no longer necessary. It’s true, that parable—it’s the wolf you feed that survives.

Walking the town that first time, a hot cup of coffee at the local diner, a warm glass of amber at the one bar in town, I felt the waves of desperation wash over me, the sickness, and the despair. No telling which came first—the dying chicken or the rotten egg—but it doesn’t really matter, does it? Was the diseased moth drawn to the flickering flame, or did the flame create chaos, burning everything that surrounded it?

The cabin.

It was a place that held my gaze, but only for a moment, because what I was looking for was something else entirely. The reason I was here. And as the darkness started to spill over the grey, frozen ground, the black spruce and lodgepole pines lining the base of the mountains, the distant bay shimmering on the horizon, I found a path that wound off the main road, behind the cabin, and into the woods. No footprints, an immaculate ribbon of white. I turned my head this way and that, looking for somebody to stop me, looking for any sign of life, but there was none. Everyone was inside—you don’t stand out in the cold here, unless you have a death wish. So I walked toward the edge of the forest, the virgin layer of snow crunching beneath the soles of my boots, and the grand archway that held the trailhead in place, an electricity filing the air, my skin suddenly warm, and flushed, a single drop of sweat running down my left temple.

I stood at the opening to the neglected trail, looking as deeply as I could down the path, and up into the slow incline that would certainly continue up the hill, rising slowly into the mountains. Across the sky, now pitch black, there flowed a curtain of lights, the Aurora Borealis, drifting and floating as if great amorphous eagles, rising and falling on thermal streams, charged particles sputtering and crackling as they swayed back and forth. In the distance something howled, most likely a wolf or coyote. I thought about where I might bed tonight. I thought about sharp teeth and weak flesh. I thought about hunger, and desire, and vengeance. I listened to the promises the lights made to me, the deal we were about to broker, and the history of this land spilled out across the wavering streaks, as they changed from yellow to green, with just a splash of red. We would palaver for some time, the lights and I, warnings made, uncertainties broached, a smile creeping across my face, as we came to an agreement.

I nodded my head, and took a few steps back, as the lights faded into the night, and a ripple formed at the opening to the trail. It was subtle, a glimmer of gold thread, an oily smear that started at the top of the archway, the slender trees bent over, holding each other in the cold, empty space, running all the way to the ground. It was starting already. Though the long night hadn’t officially begun yet, still a few days away, the tear was already forming. And from that rip there emanated a rush of heat, as if a long, hot breath had been slowly exhaled, rotten eggs, meat gone sour, a ripeness that made my nose wrinkle, and bile rise up in my throat. And wheezing through the slender gash was a screech and bellow filled with anger and remorse, some great venting created out of anguish and hunger, an eagle cry over a grizzly’s roar that ended as quickly as it started. A ripple of goosebumps ran over my skin, and I backed away from the breach.

I had to get started. There wasn’t much time.

And so I took the cabin, bought it outright for a song and a dance, and quickly got to work.

•••

The cabin.

It wasn’t much, but it had potential—proximity, simplicity, and away from prying eyes. It would do.

They told me it had been built by hand—by one of the locals, a man who hunted and fished like so many do here, a place to build a fire, lay his head, and be left alone with his thoughts. The logs were cut from the towering spruce that filled the space around us—sawed and hewn, notched and stacked. Tedious hours were spent with a hammer and chisel, chinking the gaps between them with oakum and tarred cloth to keep out the unrelenting cold. The low stone wall that surrounded the base of it must have taken him days to find, carry, and stack—providing a solid structure around the bottom of the cabin, for warmth, and security, and strength. The greenery and vines that ran up the walls, the roof covered in sphagnum moss, swallowing the cabin—it drew me in, and I felt that I could work here, that I could commune, and heal, and absolve.

Stepping inside, out of the meagre warmth of the low sun, it was one main room, with a large stone fireplace to the right, a torn leather chair, and faded cloth couch filling up most of the space, simple wooden end tables, and lamps with shades that looked like leather, or perhaps deerskin. The metal shade frames held the silhouettes of wolves and caribou and bears. Stale alcohol and cigarette smoke lingered from its last occupant, blending oddly with the sweet aroma of cut wood in the cold, stagnant air. The table was simple—one huge, round stump of oak, sanded and varnished to a shiny hue. It must have weighed a ton. I almost tried to lift it up in order to see if there were roots sinking into the floor and earth below it.

At the other end of the space was what would have to be my kitchen—a small counter with a steel sink, and a faded blue propane refrigerator that felt out of place, from another time—rounded edges and shiny chrome, standing out like a jewel that had been dropped in the dirt. Inside it were jars of expired herring, ketchup, mustard, and soy sauce. There was a full-sized bed tucked back in the corner, and a singular door that opened into a tiny bathroom. It was more than I needed.

The man killed himself, they told me. So I stood in the doorway, soaking up the space, speaking to the spirits that lingered, asking them what they might need, offering up what I could, blessings and forgiveness, as I eased over to the fireplace, dry kindling, and dusty logs still in place. With a box of matches that I found in a kitchen drawer, I opened the damper, dragging the wooden stick across the rough, black edge of the box, and lit the fire to break the chill. I walked around the space, inhaling and exhaling, but not taking a bite. There wasn’t much here for me, but I chewed on what I could find, and then spit into the warming room a grey mottled moth, with rings of yellow, that looked like eyes. It fluttered and danced in a circle before landing on my outstretched hand.

It was all that was left of him.

Lingering, uncertain, and unhappy.

He had been a lonely man, seeking peace in his isolation, and instead, finding a lifetime of regret and remorse. This was not the plan he had in mind, and as the weeks unfolded, the lake slowly freezing from the shore outward, the wild game quickly disappearing. He found that there wasn’t much left for him here. Or anywhere else it seems. The endless nights and constant snowfall have driven many a man to empty his last bottle and stare into the narrow darkness of his rifle.

Turns out it’s pretty easy to undress, walk out into the cold, and freeze to death. I turn my eyes to the two windows over the kitchen sink, gazing out into the land behind the house, through the intricate patterns of frostwork on the glass, and the woods beyond it. He walked until he couldn’t feel anything anymore, floating along on legs deadened by the cold, and then, in a moment of panic, he turned around, changed his mind, and tried to make his way back down the mountain, down the trail, to his warm cabin, and the promise of a new day.

He didn’t make it.

I stare at a patch of grass out back, the shape of the weeds and faded flowers now making sense to me. A simple man, with a sad little life, that amounted to nothing, in the end.

The moth flutters on my fingertip and takes off into the air.

Maybe it’ll stay.

Maybe it’ll wander out the door.

Either way, it won’t be here long.

I take a deep breath, and a blueprint appears in my mind.

•••

Knowing I only had a few days to fortify my homestead before the long night arrived for good, I did what I could to strengthen my abode.

I brought a few things with me, but the rest I would have to acquire in town.

It started with the fresh herbs, and a slow circling of the cabin. It burned and smoked, the windows open, the door wide, my mind seeking out the presences that still lingered, the last remnants of death and loss—the man, his few friends, the neighbor who found him, the handful of women that spent time with him, the lost souls that lived here briefly after he was gone—all of it must be cleansed, and escorted out, to make room for other speculations. It didn’t take long to walk this cabin, inch by inch, foot by foot.

And then I was outside, examining the perimeter of the structure, taking notes as I went—stones to be put back in place, logs to be nailed down, cracks filled. There was a ring of bushes that ran around the entire property, part of what drew me to this space. I walked the circle and touched the shrubs, seeing the work that the man put into this property. The holly was tucked up tight from one bush to the next, red berries popping out like dots of blood. The circle was complete, but for the opening that let me in. A stone path lead from the front door straight forward and through the opening in the bushes, and down the front yard all the way to the dirt and gravel road that meandered into town. And then farther out from the bushes were evergreens—juniper, and spruce, and pine.

It was a good start, and it would help, but I had to do more.

It started with the salt. There were a few tools in a tiny shed behind the house including a variety of shovels for clearing wet, heavy snow from the cabin roof in order to keep it from collapsing, and so I took my supplies and began digging a shallow trench just inside the ring of bushes, all the way around the house. The ground wasn’t quite frozen yet, but it would be soon. In the bright sunlight I worked up a sweat chipping at the surface ice with a pickaxe, digging deeper into the soil beneath with the shovel, my arms burning, my back aching as I go. By the time I was done, the sun had gotten much lower in the sky, and my feet throbbed in my work boots, my jeans dusted with dirt, my blue flannel draped over the bushes, only a black t-shirt between myself and the elements. The moment I stopped digging, the cold rushed in, as it always did, and I took a moment to survey my work.

It would do.

Walking backwards I took the 50-pound bag of salt and started to fill in the trench, sprinkling a solid line all the way around the property, completing the circle as overhead hawks circled, marking my progress. To the ring I added a number of herbs, flowers, and seeds—dill, rosemary, lavender, fennel, and rue. If you were standing in my kitchen you might just think I liked to cook, my herb garden now filling the space above the sink, and under the window. You might notice the purple flowering bushes, and spiky plants, and think I had a green thumb.

When I finished, and looked up, the sun has gone, and I was suddenly cold. It was not dangerous yet, but it would be soon. It would be easy to get caught out, and I shivered as I hunted down my flannel, eager to get back inside to the fire that burned brightly, a plume of smoke rising up out of the chimney like grey tendrils.

Later, when the moon hung overhead, and the animals gathered at the edge of the woods, watching and waiting, I would return with water, trucking buckets from the nearby river where I kept a hole chopped all winter, one bucket after another, and slowly filled the trench, the ground certainly frozen now, as the temperatures had dropped, the sun long gone, dipping down below freezing, and into the teens, the wind whipping in over the water, and up the hill, cementing this moat that I had built around my house.

It would hold the salt, so that it wouldn’t blow away. It would complete the circle, as the herbs and flowers blended together. It would close a loop that I was desperate to finish, so that I might sleep tonight, my muscles aching, my mind reeling, as the aurora dances over the horizon and the tear slowly widened.

•••

Every location is unique. I’ve spent time in the crippling heat of the desert. I’ve spent time in the crushing blanket of humid swamplands. I’ve spent time in thick woods that felt ancient and undisturbed. They all have something to offer, and different ways of taking. Here, in the cold, the far north, the brutal winds and interminable winter, there are unique challenges to this work. So on that first week, as I prepared for my first meal, I wandered the landscape to see what I might find—allies, enemies, resources, and traps.

I would not be disappointed.

With that first long night approaching, and the cabin secure, I decided to take a walk to explore my immediate surroundings. I bundled up in jeans and long underwear, two pairs of socks, my work boots, a thick turtleneck, a heavy sweater, knit hat, insulated gloves, and a parka over the top. I would learn about cold and rain, about ice and sleet, how to layer better, but that would take time, and I’d make mistakes. Everyone does; frostbite was inevitable here. It only took a tiny gap in the clothing, an inch of exposed flesh. The pin-and-needles came first, then the numbness before it started to burn and swell. It would turn a waxy white, stiff, and still cold to the touch, even after you were warm again inside the safety of your cabin. A day later, the blisters would form, ugly and angry, without relief. If it got down deep enough, the flesh turned black as coal and hard as old ice, as the skin slowly died. It only took losing one finger, or one toe, to not make that mistake twice.

Or so I’ve been told.

With the woods to my back, it seemed the obvious place to start. So I started my hike with the sun high overhead, passing through the archway that led into the encroaching forest, the rift hardly a flicker in the brightness of day.

The path was well trodden, and I wondered what might draw the locals up into the woods, into the hills and the craggy mountain that lurked with such a heavy presence. The further I hiked up the trail the quieter it got. The chirps and calls, the fluttering and rustling, faded into the background. The skittering of small woodland creatures disappeared as the forest grew thicker, and darker, around me. I had assumed that once I started to climb the mountain proper that it would all thin out and start to die off, the thinner the air, the higher I went, the colder it got. But not yet. For now, the bushes, and shrubs, and foliage closed in tight. It was both comforting and claustrophobic.

It took a while for me to notice its presence, so focused I was on maintaining my footing on the icy slope, pushing my way through the snow-laden spruce boughs. My pulse throbbed in my neck the higher I hiked, the more I started to sweat, unzipping my coat, and stopping at a gap the trail, a natural overlook that exposed the rocky beaches, and the shimmer of the bay below, and the ocean beyond it.

I smelled it first, something ripe and musky, a blend of damp hay, dirty dishrag, and wet dog. In the distance branches snapped, and dense foliage brushed up against something, a gentle whooshing sound, and then a heavy trembling in the earth. My eyes darted from the water to the trail, up and down, back to the woods, trying to gaze as deep into the greenery as the forest would let me. The pine and spruce swayed in the breeze, creaking and bending, as they moved. Birds cawed overhead, a rustling of black wings fading as they flew away.

I considered going back, but I’d hardly gotten started, and so I continued on, up the trail, higher and higher, the incline gradually steepening.

I passed a downed hemlock tree, snapped in two, a black scar running down one side. It had fallen across the path, blocking my progress, so I paused for a moment to consider moving it.

It was way too heavy, and as I tried to lift it, estimating the weight, I noticed three scrapes, long drags of exposed wood and missing bark.

I could duck under and keep going, or I could turn back. The wind picked up, and heavy clouds drifted over me, a storm sliding down the mountain, out of nowhere it seemed, as the temperature dropped, chilling my skin.

The day was moving quickly, faster than I thought, some bit of time lost out here, perhaps, in my thoughts, under the spell of nature, and so I started to head back down.

After a few minutes I noticed a pile of scat in the center of the trail. It had not been there before, on my way up. This was not a rabbit, not a coyote. It was something else entirely. The lumpy pile steamed in the cold air, pieces of white stuck in the slimy, glistening pile of dark matter. Bones, teeth, something sinuous, fur, hair—I didn’t like any of it. It seemed unnatural, not of this place. This wasn’t a bear or a lynx. This was something else entirely.

Suddenly I wanted to be down off the mountain. In my hurry to prepare the cabin, I must have missed something. Just because the tear was small now, didn’t mean that this was the first time it had ripped. I had made a mistake. I assumed I had been called here at the inception, the tipping point, the first time this point had manifested.

I was wrong.

I had been slow getting here.

I was late.

And in that moment, I smiled, and laughed, thinking about how embarrassing it would look to run screaming down the hill, scared of a fallen tree, a pile of crap, and some strange noises, and smells, emanating from the woods.

“Take it easy, Sebastian,” I whispered to myself.

And then I saw it.

It faded into focus, not twenty feet from me, hidden in the brown of tree bark, blended in with the dirt and dead leaves, two massive horns branching up into the sky. A moment ago they were merely that—branches, two red glowing eyes just berries, a snort and heavy breath filling the air with copper, sour anger, and decaying teeth.

I ran.

I ran down the hill, trying not to trip, bulky in so many layers, my boots catching roots and embedded rocks, not looking back, but listening, oh how I listened, my ears straining to stay behind me, reaching back into the forest to try and understand if it was going to come after me, or stay where it was. Perhaps it had just eaten, maybe it was tired, or just territorial. It certainly hadn’t been following me, stalking me, as I wandered about the woods and trails.

Something to the left caught my eye, and I hesitated to look, needing to stay focused on the path, but I glimpsed the red, the glistening white, and kept my gaze on the broken limbs of a doe, head wrenched into a twisted knot of fur and muscle, eviscerated and lying in the leaves, guts strewn about as if being searched for something elicit, some gem or drug or buried secret, intestines loping out in long strands, the broken legs sticking up at odd angles, its eyes open wide, tongue lolling, a long dead cry and bleat buried in its throat.

And then I was tripping and stumbling, hands held out in front of me, the archway at the end of the forest in sight, the rip winking, the gold filament reflecting the sun, and I barreled through the opening, head turning back to see what must certainly be upon me by now.

I was suddenly falling, onto the dying grass, onto my face, arms outstretched, turning over, my mouth open and ready to scream—and there was nothing. Just the snowy silence and the first drops of freezing rain, clouds rolling in to blot out the sun. I heard voices down the hill—fishermen, hammers banging, a loud lid slamming shut, the honk of a horn, and laughter, a tarp rippling in the wind, being tied down no doubt, and my breath—heavy and fast accompanying a pain that rifled through my chest.

I wasn‘t alone out here.

I thought I had more time, that it hadn’t started yet.

But it was already happening here, it seemed.

It was time to eat, I feared.

But I had no banquet to attend.

I would have to improvise, and fast.

It had already come through.

And there might be others.