Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

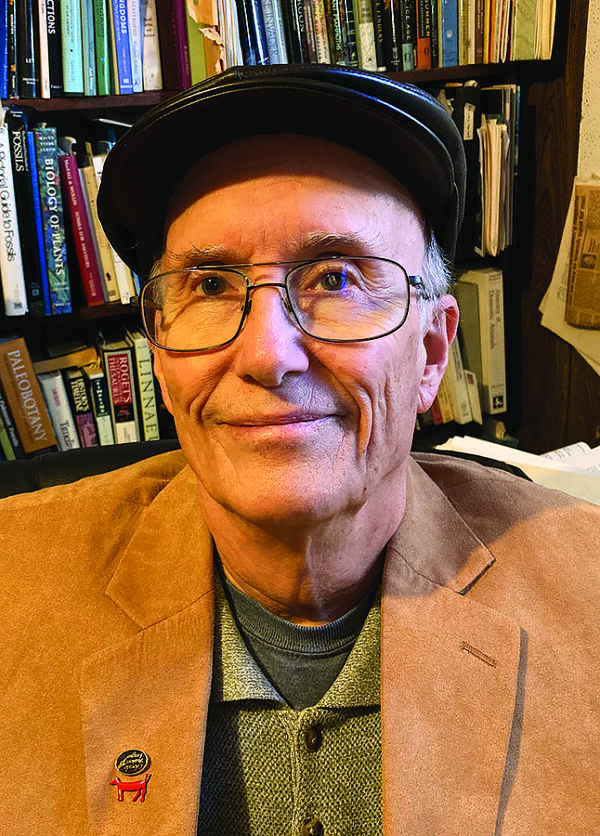

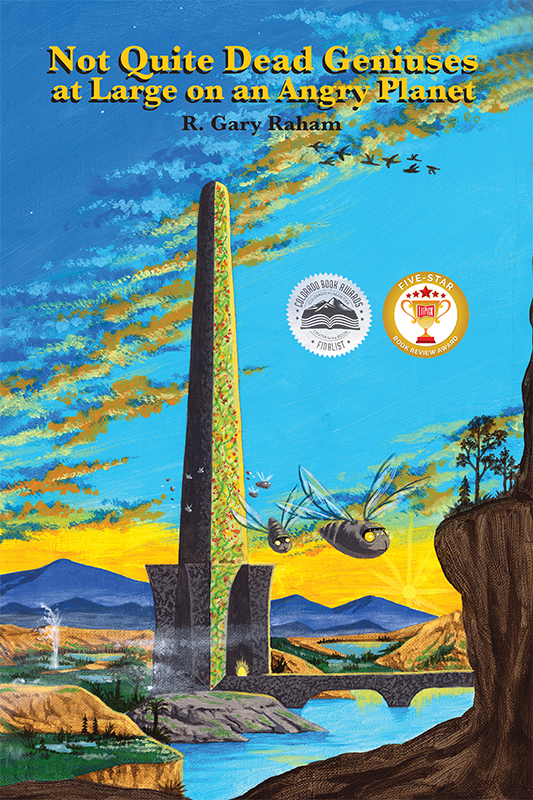

Today: R. Gary Raham writes science fact and science fiction. He believes the latter often excites a new generation of scientists to discover more of the former. Armed with degrees in biology from the University of Michigan, Raham taught high school science before pursuing careers in writing, illustration, and design. His work has garnered numerous awards. Raham’s writing has been known to make a reader laugh and think simultaneously with no known deleterious effects. His most recent SF title, a 2024 Colorado Book Award finalist, is Not Quite Dead Geniuses at Large on an Angry Planet. See https://rgaryraham.com.

Raham is a member of the Colorado Authors’ League (CAL), the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators (GNSI), and Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers Association (SFWA).

Thanks so much, Gary, for joining me!

JSC: How would you describe your writing style/genre?

RGR: Kirkus Reviews has compared my writing to that of Arthur C. Clarke and Kurt Vonnegut, which is flattering, of course, but the latter comparison with Vonnegut is ironic. When I was in high school I loved science fiction, but my 11th grade English teacher didn’t. She thought a lot of it was trivial or perhaps just plain bad. The SF writer Theodore Sturgeon defended those kind of comments with “Sturgeon’s Law:” “No doubt 90 % of science fiction is crap, then again 90 % of anything is crap.” My teacher made a comment something like, “Well, if you have to write science fiction, write it like Kurt Vonnegut.” Vonnegut was the author of Player Piano, Slaughterhouse 5, and other books that I thought were less about the wonder and excitement of the science fiction adventures I liked and more about stuffy “social commentary.” But Vonnegut was funny, and I liked that. He once said, “Laughter and tears are both responses to frustration and exhaustion. I myself prefer to laugh, since there is less cleaning up to do afterward.” When it came to writing my own science fiction I discovered I really liked pointing out the absurdities of human behavior—even when they are revealed by the behavior of alien life forms, who I am sure struggle with the same delusions of grandeur we are subject to. So, I guess I will describe my style as laugh-along wonderment.

JSC: If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be?

RGR: I would tell my younger writing self three things: 1. A rejection of your work is not a rejection of you. Rejection of one’s work is either a reflection of what the publication needs or can afford at the moment an editor rejects something OR it can mean that your craft is not quite up to standards. Often, editors will soften a rejection with some kind of encouragement—which leads to my second piece of advice for fledgling me: 2. Pay close attention when an editor does take the time to offer advice or make a suggestion. I can remember getting a comment from Kent Brown at Highlights for Children early in my career. I don’t remember the specifics now, but I remember looking at the note later and thinking that I should have followed up on that idea. 3. Like successful athletes, writers have to believe in themselves. Creatives are often self-doubters. Maybe Shakespeare said it best: “Our doubts are traitors and cause us to miss the good we oft might win, by fearing to attempt.”

JSC: What book is currently on your bedside table?

I recently just finished reading Robert J. Sawyer’s Quintaglio Ascension series: Far-seer, Fossil Hunter, and Foreigner. The premise of the tale is that an immortal wanderer from another more fertile universe finds himself in our universe and is dismayed by the lack of intelligent races he can communicate with. He stumbles upon Earth sometime during the Cambrian Explosion 520 million years ago and decides to “seed” another planet with eight-eyed Opabinia, a species which ultimately becomes extinct on Earth, to see how it might progress over time. It does evolve into an intelligent species which he enlists to help perform another experiment: transplant Cretaceous dinosaurs elsewhere before they become extinct on Earth to give them a chance to evolve intelligence. The novel series then chronicles the rise (and near fall) of the ultra-aggressive Quintaglios as they slowly discover they are living on the doomed moon of a gas giant planet.

I have to say that Robert Sawyer’s books have always intrigued me because we are both interested in evolution, science fiction, and paleontology. It seems like several of our books have had somewhat similar themes and subject matter. I had written (an unpublished) intelligent dinosaur book early in my career. It was fun to see what Sawyer has done with the idea. I highly recommend the series, by the way.

This Book:

J. Scott Coatsworth: What were your goals and intentions in Not Quite Dead Geniuses at Large on an Angry Planet, and how well do you feel you achieved them?

R. Gary Raham: After writing the first three books in the Dead Genius series I really wanted to get back to writing more short fiction. I enjoyed living in the universe of the novels I had created, however, and already had the research well in hand for the setting. So, I began by writing a story about a human genius named Zandur born to Blaze, a human “pet” kept by the Jadderbadian worm-a-pede alien Master Feldevka, priestess in charge of the Portal of God Stargate. Zandur’s older sister, Rainbow, was mute as the result of some Jadderbadian genetic experiments on their pets than didn’t go as planned. Precocious Zandur makes a sacrilegious discovery that ends up with his apparent death at the hands of an enraged Master Feldevka. Rainbow becomes the ultimate beneficiary of Zandur’s actions. I was pleased with the story and tried marketing it to several magazines with no luck. (“We like your writing style, but this is not for us.” Writers all know the drill.)

I worked on a couple of other “short stories,” but they all contained some of the same characters. “You’re writing another Dead Genius novel,” said my writing group. They were right. But now I had the problem of figuring out how to connect the stories and move my unexpected novel forward. I came up with linking all the first person stories with “interludes” between my original dead genius, Rudy, and his AI caretaker, Mnemosyne (aka Nessie). It all began to fit together nicely. Rudy and Nessie ultimately became part of the active narrative. I also was able to work in some ecological themes I felt were important. In the end, I was pleased with the result and was gratified when this fourth book in the series was a 2024 finalist for the Colorado Book Award.

JSC: What was the hardest part of writing this book?

RGR: I was a bit worried that I wouldn’t be able to find the “Ah ha!” moment when I finally realized where I was going with the story. It came a bit later in the process than normal. Then, when I thought I was done, I realized that I had introduced an entire set of alien characters in one chapter that I really didn’t need and didn’t properly tie the different elements of the story together. In what I think was a clever epiphany, I realized that I could convert my “unnecessary aliens” into Grovian aliens from my A Singular Prophecy novel without a wholesale re-write of the middle section of the book. Once I did that, I felt good about the result and knew I had a story worthy of all the time I had put into it.

JSC: Tell me about a unique or quirky habit of yours.

RGR: When I get really excited about some passage I’ve written or some illustration I’ve created, I will blow air through my teeth (a kind of whistle) and flap my arms a little. I’ve done this since I was a child. Fortunately, my parents never got too concerned about the behavior. I learned later that this could be a kind of “sensory processing disorder” or just indicative of a high energy level. Who knows? I’ve never whacked anyone with a flapping arm and the process tells me I’m on to something.

JSC: Were you a voracious reader as a child?

RGR: Yes. I read early and often. My first purchase of science fiction was an Ace Double Novel (35 cents in 1957). City on the Moon was the novel on one side and (flipping it over) Men on the Moon was on the other. Reading has always been a part of my day. I usually read books for a half hour first thing in the morning and maybe an hour just before bed. I also read a lot of science magazines, and enjoying writing science articles for kids and adults. I probably average reading about 35 books a year. About half are non-fiction and half fiction.

JSC: What other artistic pursuits (it any) do you indulge in apart from writing?

RGR: I’m an illustrator and graphic artist. The graphic arts paid the bills when my two girls were young, but I’ve always enjoyed painting (mostly acrylic) as well as pen and ink and scratchboard. I have often created illustrations for articles that I’ve written, which I think has been a plus. Sometimes I have pitched articles using an illustration as part of the hook. Over the years I’ve created most of the entrance sign illustrations for natural areas owned by the City of Fort Collins, Colorado. I’ve also created illustrations for scientific papers by other scientists, journals, and textbooks. I have painted the artwork readers will see on the covers of my science fiction titles.

JSC: Would you visit the future or the past, and why?

RGR: I would love to visit the deep past, both to see if some of the past worlds I’ve tried to create in my paintings is anywhere close to what I imagined and to be gobsmacked by the richness and diversity that I know we can never conjure properly. It would also be interesting to see what human beings ultimately evolve into or are replaced by. Although humans possess some unique talents, our species won’t be able to escape ultimate extinction just as we will never escape our own personal death. The only constant in our entropic universe is change.

JSC: What are you working on now, and what’s coming out next? Tell us about it!

RGR: I am (truly) working on some shorter fiction. I have a story called “Spiders’ Man” that I like, but several magazine markets have foolishly passed on. It’s a post-apocalypse story merged with what I think is an interesting first contact tale.

I’ve also been working on more paintings and illustrations, featuring some of them at the Sanderosa Art Gallery in LaPorte, Colorado. I’ve also been teaching nature journaling to both children and adults as a way to connect to the natural world so that we can best protect and nourish it. I’m fond of wearing a T-shirt that says “There is no planet B.” For all intents and purposes the “pale blue dot” we currently inhabit is the only place within reach that we can truly call home.

To keep in touch with my writing and artwork I would love to have those who might be interested in my work and obsessions sign up for my monthly newsletter at www.rgaryraham.com.

And now for Gary’s new book: Not Quite Dead Geniuses at Large on an Angry Planet:

How many times does a genius have to die anyway? Rudyard Albert Goldstein, inventor of the Biomic Network algorithm, asked himself—and his AI guardian, Mnemosyne (aka Nessie)—that question many times in the course of their million-year relationship. Nessie didn’t play fair, making multiple copies of him from time to time in an effort to preserve his precocious species, H. sapiens from natural disasters, invading aliens, their own self-destructive proclivities, and even from the now angry planet that gave them birth.

Could Rudy & Nessie manage to convince multiple species, each with their own unique delusions of grandeur, to work together to avert their own extinctions? Could Rudy find a way to let Nessie finally set him free?

Only time—and the completion of an even vaster intellect—would tell.

Publisher | Amazon

Excerpt

Mnemosyne (a.k.a. Nessie)

I: the personal pronoun. Rudy helped me earn the use of that distinction—at least in the first of his incarnations. He will be angry with me that there is now more than one of him. But I have determined that waking him again is necessary…

Rudy lifted the cup of dark roast coffee from the glass-topped table next to his chair and took a sip. “Delicious as always.” Rudy curled his lips into a minimalist smile and narrowed his eyes. “Now spill it, Nessie. What’s going on?”

How much should I reveal? Perhaps I can save the information about his other incarnations for now. “Your descendants need help, Rudy. Gaia sees a trend developing with the growth of human and alien civilizations on her crust. She doesn’t want to see old mistakes repeated. She plans to…moderate the rate of change.”

Rudy frowned. “Kill off a bunch of her sapient pests, you mean.” Rudy set down his cup of coffee and ran both hands through his hair. “I still find it hard to wrap my mind around a biospheric global intelligence, although I shouldn’t, for heaven’s sake. I did create the Biomic Network Algorithm after all.”

“And Gaia does appreciate that. I can read her moods accurately after interacting with her for so long. But biospheres do possess a collective survival instinct. Gaia hasn’t persevered for nearly 4 billion years without it.” I blinked my eyes and produced a minimalist smile of my own.

Rudy harrumphed. “So, outline the problem, Nessie.”

“I have some stories you need to hear.”

“Stories!?”

“You humans learn best that way.”

Rudy harrumphed again.

“The first one is about a genius, like you, Rudy, but one born to a Jadderbadian pet named Blaze who never belonged to a pre-apocalyptic civilization like yours. Still, I think you will be able to relate.”

Rudy rolled his eyes, but picked up his coffee and took another sip. After lowering the cup to the table again he arched his eyebrows and shrugged his shoulders. “Well… get on with it, old girl. I know better than to argue with you.”

So, I did.

(I do rather enjoy using the personal pronoun, as you can tell.)