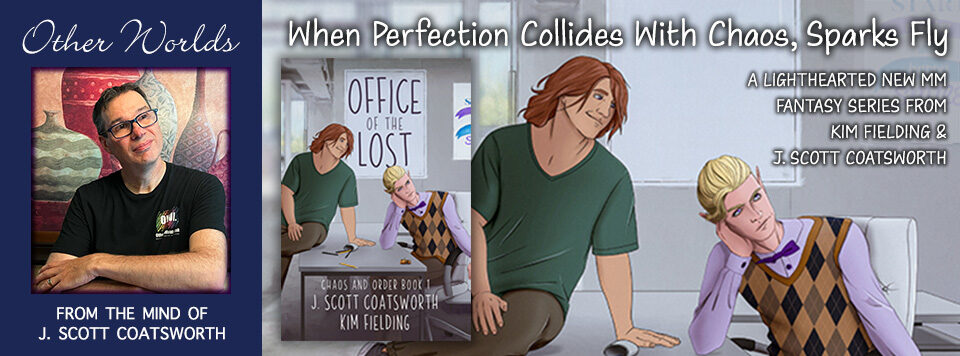

Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

Today, Janelle Reston – Janelle Reston lives in a northern lake town with her partner and their black cats.

Thanks so much, Janelle, for joining me!

J. Scott Coatsworth: Do you use a pseudonym? If so, why? If not, why not?

Janelle Reston: Yes. I write under several different genres and for different audiences, so I divided them into general groupings and assigned different names (pen names and variations on my legal name) to each. I did this to make marketing my books easier, but I think it may actually be harder …

JSC: If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be?

JR: Write a lot of crap. Don’t wait until the idea is perfect.

JSC: Do you ever base your characters on real people? If so, what are the pitfalls you’ve run into doing so?

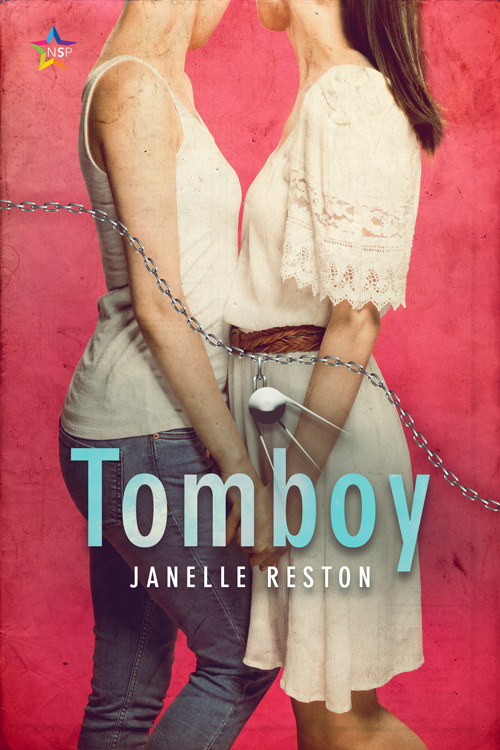

JR: Only vaguely. For my novelette Tomboy, which is a coming-of-age romance set in the 1950s (and not erotic—go figure!), I drew on some stories my parents and other relatives told me about the era. Some of the fashions mentioned were probably inspired by things from my mom’s childhood that she unearthed from storage when I was nine or ten years old. The central character, Harriet, is a little like my mom in her love of Gunsmoke and her not-interested-in-putting-up-with-other-people’s-bullshit attitude, but otherwise they don’t have a lot in common.

JSC: How long do you write each day?

JR: Zero to eight hours.

JSC: Do you reward yourself for writing, or punish yourself for failing to do so? How?

JR: Neither. Writing is an award in itself, and as a general rule, I don’t think punishing adults for picadillos is a productive strategy.

JSC: Do you read your book reviews? How do you deal with bad or good ones?

JR: I try not to, though I will read them if a reviewer or my publisher sends me a link. But if one needs to edit their book’s page on Goodreads by adding a new edition number or a new format, there’s always the risk of accidentally reading one if you don’t squint your eyes.

That’s how I ended up reading a review on Goodreads for my book Tomboy that was written by someone who clearly hadn’t read the book, just the blurb. (The main character’s father sympathizes a bit with communist beliefs; the reviewer thought that meant the same thing as “Nazi sympathizer” and concluded that the book was pro-Nazi propaganda. Oh my.)

At the time I read that review, it was the only one up on Goodreads. Fortunately that has since changed.

JSC: How long on average does it take you to write a book?

JR: I don’t really track that. There’s so much that goes into writing a book than writing it. There’s editing, working with publishers, promoting it … plus books come in many different lengths. So yeah. No idea, but I’d guess at least a hundred hours for a first draft of a full-length novel.

JSC: What do you do if you get a brilliant idea at a bad time?

JR: I never have brilliant ideas. I just have ones that interest me. Whether a story turns out to seem inspired by brilliance depends on the work I put into it.

JSC: Why did you choose to write in your particular field or genre? If you write more than one, how do you balance them?

JR: When it comes to choosing genres, I’m like a dog presented with several squirrels, a dead fish, a pile of dirt to dig, a squeaky toy, and treats. I don’t choose, I just lunge for the closest thing. And I definitely don’t balance things. I wouldn’t even know what that meant, or where to begin.

JSC: Are there underrepresented groups or ideas featured if your book? If so, discuss them.

JR: Do lesbians count? In my erotica collection, I also have a Deaf domme of color (and another domme of color who’s hearing), a black witch, ex-Amish and Latina bakers, and nerdy genderqueers who are a little too obsessed with The X-Files. I tend to write lots of different types of characters because I know lots of different types of people.

JSC: What were your goals and intentions in this book, and how well do you feel you achieved them?

JR: To unashamedly explore female desire. I think I did pretty well, but that’s really up to the reader to decide.

And now for Janelle Reston’s book: Tomboy:

Some kids’ heads are in the clouds. Harriet Little’s head is in outer space.

In 1950s America, everyone is expected to come out of a cookie-cutter mold. But Harriet prefers the people who don’t, like her communist-sympathizer father and her best friend Jackie, a tomboy who bucks the school dress code of skirts and blouses in favor of T-shirts and blue jeans. Harriet realizes she’s also different when she starts to swoon over Rosemary Clooney instead of Rock Hudson—and finds Sputnik and sci-fi more fascinating than sock hops.

Before long, Harriet is secretly dating the most popular girl in the school. But she soon learns that real love needs a stronger foundation than frilly dresses and feminine wiles.

Buy Links

Excerpt

The first time I met Jackie, I thought she was a boy. Of course, she was only eight then, an age when most humans would still be fairly androgynous if our society didn’t have the habit of primping us up in clothes that point in one direction or the other.

Jackie was in straight-legged dungarees, a checkered button-down shirt, and a brown leather belt with crossed rifles embossed on the brass buckle. Her hair was short, trimmed above the ears.

“Who’s that new boy?” my friend Shelley whispered as we settled into our desks. It was the first day of fourth grade, and Mrs. Baumgartner had made folded-paper name placards for each seat so we’d know where to go. Shelley always sat right in front of me because our last names were next to each other in the alphabet. She was Kramer; I was Little.

I looked at the blond cherub in the front row. He—as I thought Jackie was at the time—had his gaze set toward the ceiling, eyes tracing the portraits of the US presidents that hung at the top of the wall. A cowlick stuck up from the back of his head. He reminded me of Dennis the Menace, the mischievous star of my new favorite cartoon strip, which had debuted in our local paper that summer. I liked the way Dennis talked back to adults but somehow never got in trouble for it. I wished I had the same courage.

Mrs. Baumgartner walked into the room. The class fell silent and we straightened in our chairs, facing her. “Good morning, class. I’m your teacher for this year, Mrs. Baumgartner.”

“Good morning, Mrs. Baumgartner,” we answered in unison. She spelled her name on the chalkboard in cursive and asked us to recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Back then, the Pledge didn’t have the gist of a prayer like it does today; “under God” wasn’t added to “one nation indivisible” until three years later, after Eisenhower became president. I wiggled my toes around in my hand-me-down saddle shoes as we recited the words.

The trouble began when Mrs. Baumgartner started to take attendance. “Jacqueline Auglaize?”

“Here, Mrs. Baumgartner,” Dennis the Menace answered from the front row.

Mrs. Baumgartner narrowed her eyes. “New year at a new school, and we’re starting with the practical jokes already?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Will the real Jacqueline Auglaize please speak up? This is your only warning.” Mrs. Baumgartner’s eyes scanned the room. I craned my neck around. I hadn’t noticed any new girls in the classroom before our teacher’s arrival, but maybe I’d been distracted by the Dennis the Menace boy.

“I’m Jackie Auglaize, ma’am,” Dennis the Menace piped up again.

Mrs. Baumgartner’s face screwed up as if she’d accidentally sucked on a lemon. “What you are is on the way to the principal’s office, young man.”

“I’m not—”

“And a detention for talking back.”

Mrs. Baumgartner called on one of the other boys to escort the new, nameless student to his punishment. From chin to scalp, Dennis the Menace’s face turned red as a beet. His flushed ears looked almost purple against his pale hair.

Kids playing pranks didn’t blush like that.

“I think that really is a girl,” I whispered to Shelley. But if she heard, she didn’t respond. She knew better than to turn around in her seat when a teacher was already angry.

An hour later, Mrs. Baumgartner was quizzing us on our classroom rules when the school secretary appeared at the door. In tow was a student in a frilly cap-sleeved blouse, knee-length blue corduroy jumper with a flared skirt, lace-trimmed white bobby socks, a pair of shiny black Mary Janes—and short blonde hair.

The cowlick stood like a sentinel at the back of her scalp despite the hair polish that had clearly been combed through since we’d last seen her.

An audible gasp filled the classroom. Actually, it was multiple gasps, but they happened in such synchronization that they had the effect of a single, sustained note.

“Mrs. Baumgartner,” the secretary said, “Jacqueline Auglaize is ready to return to the classroom. We’ve explained the school dress code to her mother. The behavior of this morning won’t be repeated.”

“Thank you, Miss Hamilton. Welcome back, Jacqueline.”

Titters filled the room as Jacqueline walked toward her desk. Mrs. Baumgartner slapped her ruler against her desk. “Does anyone else want a detention?”

We went quiet. Detentions are never an auspicious way to start a new school year.

We spent the rest of the morning learning how to protect ourselves from atomic explosions. Mrs. Baumgartner said this knowledge could save us now that the Soviets had the bomb. “When an air raid siren goes off or you see a bright flash of light, duck and cover underneath a table or desk, inside a corridor, or next to a strong brick wall. Then pull your sweater or coat up to cover the back of your neck and head,” she explained.

We all squatted under our desks as instructed. My father said the Russians weren’t stupid enough to bomb us, that they loved the common people and wanted to protect us. But Mrs. Baumgartner seemed to think they were. She went on in excruciating detail about the things that could happen to us if we didn’t duck and cover. Glass from broken windows could fly in our faces, we could get a terrible sunburn from the blast; pieces of ceiling might drop on our heads. I wasn’t sure whom to believe about the bomb—my dad or Mrs. Baumgartner. I didn’t want to think about it. I shut out my teacher’s voice and stared at my scuffed saddle shoes, pondering how a boy could magically turn into a girl in the wink of an eye.

“She’s not a girl,” Shelley insisted as we walked out to morning recess. “Girls can’t have hair like that.”

“They can if they cut it.”

“But no mother would let a girl wear her hair so short.”

“The school wouldn’t let a boy wear a dress to class.”

Shelley must have been won over by my logic, because the next thing that came out of her mouth was, “Maybe she has a little brother who likes to stick gum in people’s hair.” Shelley’s brother had done that to her once, but since he only got it on the tail end of her braid, she hadn’t lost much length to the scissors when her mother cut it out. “Or she got lice. Yuck.”

I didn’t like the direction of Shelley’s last comment. As it was, the new girl was guaranteed to have very few friends after the morning’s clothing incident. If the lice rumor spread, she’d have no friends at all. I’d been new once too.

“She doesn’t look dirty,” I said. “Maybe her hair got caught in an escalator and they had to cut it off.” I was terrified of escalators. My mother had warned me never to play around on one or my clothes would get snagged between the steps and I’d be pulled in, then smashed as flat as a pancake. Back when she worked in a department store, before marrying my dad, she saw a lady get caught by the scarf in an escalator’s moving handrail, and it would have been death by strangling if an alert gentleman with a penknife hadn’t been nearby to free her. I still get a little on edge every time I step onto one.

We got in line to play hopscotch on a board a couple other girls had drawn earlier that morning. I looked around. The whole school was out on the playground, and it was harder than I would have expected to find a short-haired girl in a blue jumper. There were lots of blue corduroy jumpers darting around the swings and monkey bars and jungle gym. Wanamaker’s must have featured them in its back-to-school sale that year. My dress wasn’t new. It was a hand-me-down from my older sister, with a ribbon tie and a skirt made with less fabric than the newer fashions. Shelley and I had done a test run of our first-day outfits the previous week, and no matter how fast I spun around, my skirt failed to billow as dramatically as Shelley’s.

Still, I tried to make the skirt swing gracefully as I hopped down the squares. I had no desire to be dainty, but I liked the aesthetic of fabric twirling in the air. We went through the hopscotch line four times before I finally spotted Jackie. She was over by the fence, poking at the dirt with a stick. Alone.

That last bit was no surprise.

It took three more rounds of hopscotch before I worked up the nerve to go find out what she was doing.

“Where are you going?” Shelley called as I marched off.

I didn’t answer her, afraid I’d lose my momentum. It was risky talking to an outcast. On the one hand, it was the only way to turn her into not-an-outcast. On the other hand, it might turn me into one too.

“What are you doing?”

Jackie looked up. “Thinking about digging a hole to China.”

“I don’t think you can actually—”

“I know. My uncle says I wouldn’t want to go there anyway. Not with all the Reds.”

My parents sometimes talked about Communists over the breakfast table. My dad didn’t think they were that bad. He said if it hadn’t been for the Russians, he’d still be overseas fighting the war, or dead. Besides, the Communists were right about the whole religion question. Mom hated when he talked like that and warned me never to mention my father’s opinions to anyone outside the family. So I didn’t. “What are you actually doing, then?”

“Digging a trench.”

“Why?”

Jackie shrugged. “Something to do.”

I found another stick and squatted down next to her. The exercise seemed pointless, but I dug along right beside her. My dad had spent a lot of time digging trenches in the war. Maybe digging trenches would help me understand him. I’d asked my mom once why Dad got so sullen sometimes and my mom said that the war had changed him, that before he went he’d been a happy and hopeful young man, that his laugh was so buoyant it seemed to lift her up, made her feel like she could fly. I couldn’t remember ever hearing my father laugh like that. He sometimes chuckled when reading the funnies or when we listened to The Great Gildersleeve on the radio, but it was short and almost inaudible, like a stifled sneeze.

Jackie was humming to herself, some song I didn’t recognize. She seemed to be off in another world, her eyes focused on the patterns her stick made in the dirt as if they were a cryptogram that would disclose the route to a hidden dimension. I thought she was being rude. If we were going to play together, it should be together and not just side by side. I tried to come up with a song we might both know, but her tune kept me from remembering the hundreds of melodies I kept stored in my head. I decided to get her to talk to me instead. “Why did you come to school dressed like a boy?”

She looked up at me. There was fire in her eyes—blue, I noticed now, like the flame of the pilot light in our hot water heater at home—and animosity. I hadn’t expected that. Didn’t she realize how nice it was of me to be talking to her? Did she have no idea of the risk I was taking? “I wasn’t dressed like a boy.”

I looked at her like a cuckoo bird had flown out of her mouth.

“I’m a girl. Whatever clothes I wear, that makes them girls’ clothes. Because I’m a girl. That’s what my mom says, and I think she’s right.”

I started to protest, wielding my stick like a pointer, but halfway through my argument, the logic of her words struck me. I sat back on my heels and dropped the stick to the ground. A sort of disarmament, I suppose. A surrender. “My mom only lets me wear pants on Saturdays.”

The hostility left Jackie’s face. It was replaced with pity. “It’s okay. You can do whatever you want when you grow up. Me too.” She patted me on the shoulder. “What’s your name anyway?”

“Harriet,” I grumbled. I wasn’t sure I liked being pitied, especially since I had initially approached her out of the same emotion. Our places were switched, like that time I’d been on the seesaw with my brother, suspended high in the air as he used his weight to keep his end planted to the ground—then vaulted off so his end flipped up and mine went crashing to the ground, jolting my tailbone so hard it hurt to sit for days. But Jackie wasn’t laughing at me the way my brother had with the seesaw. Her pity had a kind quality to it.

Later, I would learn the word “empathy,” and it would immediately make me think of her.

“So your mom—your mom lets you have short hair too?”

“She cut it herself.”

“Why?”

“Because I asked her to.”

My parents never did anything simply because I asked them to. Nor did any of my friends’, at least that I knew of. I filed away this piece of information, like a National Geographic correspondent studying the tribal traditions of nomads in a far-flung part of the globe. “Why’d you ask her to?”

“It got in my way when I was playing. Made my head too hot in the summer.”

I was jealous. I didn’t want to cut my hair, but there were lots of girl things I could do without, like tight shoes and having to get married when I grew up. I didn’t want to get married and have kids. I wanted to be a private investigator like The Shadow or Philip Marlowe or Johnny Dollar, or maybe a lady lawyer like Katharine Hepburn in Adam’s Rib. And I didn’t want to have to cross my legs when I sat. It made my thighs all sweaty.

But whenever I sat on the back porch with my legs open, my mother tsk-tsked and asked, “What will the neighbors think?” She worried about the neighbors a lot, especially when my siblings and I yelled at each other or my dad drank too many Manhattans and blasted his rhythm and blues records at top volume.

I asked Jackie why her mom wasn’t worried about what the neighbors would think.

“She says life’s too short to worry about that.”

“What about your dad?”

Jackie speared her stick into the dirt. “He’s dead. The Krauts killed him in the war.”

“I’m sorry.”

“That’s okay. I don’t really remember him anyway.”

A whistle blew to signal the end of recess. We ran to line up by the school’s side door, by class and in alphabetical order. A dozen kids separated Jackie and me.

“How weird is she?” Shelley whispered as we found our places.

“No weirder than you.”

Shelley balked. “I’m not weird.”

“That’s my point.”

Shelley screwed up her face like a cartoon character with gears turning in its head. Then the invisible light bulb went off. “Oh. Okay.”

Author Bio

Janelle Reston lives in a northern lake town with her partner and their black cats. She loves watching Battlestar Galactica and queering gender. You can keep up with her at www.janellereston.com