Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

Today, Ira Nayman – In another life, Ira Nayman was a skydiving WWI hero, a yak herder in the treacherous Rocky Valleys and the lead guitarist for the band The Strange Feebles. Since that other life happened in another universe, it may not be as impressive to you as it sounds. In this universe, Ira is celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of his decision to devote his life to writing comedy, in all of its forms and in a variety of media. His Web site of political and social satire, Les Pages aux Folles, has now been updated weekly for over eighteen years. The eleventh book in the Alternate Reality News Service series, Idiotocracy for Dummies, was recently self-published. Good Intentions is his sixth Multiverse novel published by Elsewhen Press. Ira is also surprised to find himself the editor of Amazing Stories magazine. Yes, that Amazing Stories magazine. I know, right? He finds his life in this universe exciting enough. The way things go, he’s probably allergic to sky…

Thanks so much, Ira, for joining me!

J. Scott Coatsworth: When did you know you wanted to write, and when did you discover that you were good at it?

Ira Nayman: I decided to devote my life to writing comedy when I was eight years old. This may come as a surprise to people who know me as a science fiction writer, but, in fact, I have written a lot more than science fiction in my life; it just happens to have been a prominent part of my writing career for the last decade or so. The first things I wrote were pastiches of Sherlock Holmes stories (which I was reading at the time). I remember I wrote them on the backs of my father’s legal-sized accounting sheets (the fronts were too busy with criss-crossing red and green lines). I wrote one story per page, three in all. I remember wondering at the time: Where do writers get enough ideas to fill longer stories?

As of this writing, I have had six novels, 11 collections of short short stories and miscellaneous ephemera published. I guess I must have figured it out.

I’ve had various positive reviews and personal feedback over the years, but I don’t know that I’ll ever truly believe that I am good at it. I have fun with it, and that’s enough for me.

CODA: Years later, I was watching an interview with British comedian Eddie Izzard. At one point, he talked about his first encounter with his comedy hero, Richard Pryor. He soon discovered that they had something in common: they both knew that they wanted to be stand-up comedians when they were four years old. Imagine my surprise. Here, I thought I was precocious because I knew I wanted to write comedy when I was eight, but I was actually already half a lifetime behind the curve!

JSC: Why did you choose to write in your particular field or genre? If you write more than one, how do you balance them?

IN: I’ve thought long and hard about why I decided to writer humour. Most eight year-olds have no idea what they want to be when they grow up, or want to be something glamorous; writing is a lot of things, but glamorous is not one of them.

The best reason I can come up with is this: like many people who pursue comedy as a career, I had a rough childhood. I grew up in a household full of anger, and I was angry and full of self-loathing for the first decades of my life. I knew that laughing made me feel good, so I wanted to make myself laugh more. Years after that revelation, I had another one: I must have thought that if I could make my parents laugh, maybe they wouldn’t fight so much.

Eventually, I expanded the concept to people in general. I used to write for a magazine called Creative Screenwriting. After 9/11, the editor sent an email to all of his writers asking for contributions to a special issue on the role of the writer in times of national crisis. I wrote an article called “Laughter is Always Appropriate” (http://www.lespagesauxfolles.ca/index.phtml?pg=30&chap=1088). In it, I discussed a variety of ways of looking at laughter, focusing on how laughing releases endorphins into the brain – making laughter a natural painkiller – and makes life a little more bearable for people. I find the idea that writing humour helps people get through their difficult lives, if only for a few hours, very appealing.

Why have I combined it with speculative fiction for over a decade? Humour thrives on the different, the weird, the unexpected, and the tropes of science fiction and fantasy allow for a lot of that.

It’s also true that speculative fiction gives me metaphors that help me say the things I want to say. For example: the trilogy I am currently working on is about aliens from another universe who are forced to immigrate to our universe because theirs is about to collapse. My aliens stand in for any people who have immigrated (which, if you go back far enough, is pretty much everybody). Why aliens? If I had told a realistic story about human immigrants, some readers would have identified with them, but others would not (if my novel was about Jewish immigrants, for instance, anti-Semites would put their own hateful spin on the story, even if they had immigration in their recent family history. Basing the story on alien immigrants will (hopefully) keep this from happening, since no reader could have a preexisting hatred for an alien race they hadn’t encountered before reading.

JSC: Do you ever base your characters on real people? If so, what are the pitfalls you’ve run into doing so?

IN: Many people are uncomfortable talking to psychiatrists because they are afraid they will be analyzed and left feeling damaged. In a similar vein, many people are uncomfortable talking to writers because they are afraid that they will be portrayed unflatteringly in a story the writer may some day work on. For this reason, when I was younger, I steadfastly refused to base characters in my fiction on real people. Being a generally shy person, I didn’t want to be socially disadvantaged by my choice of life’s purpose.

But one day I was talking on the phone with a friend who had just had a traumatic breakup with her boyfriend. I gave her some suggestions for how she could build a ritual that might help her get over some of her darkest emotions. When she rang off to do a bit of research, I got to thinking that this might be the basis of an interesting story. The next time we spoke, I asked her if she would be okay with me writing a story based on her experience. She responded, “You know, I’ve always wanted to be a character in one of your stories.”

Hunh.

Now, what I usually tell people I meet after I introduce myself as a writer is that I will not guarantee that something they say or do won’t end up in a future story, but they have nothing to worry about. The way we build characters, we take a little bit from here and a little bit from there; not enough so that they are likely to be traced back to their source. I have never had a complaint.

I have only had one exception to this approach: the main character in my first novel is based on my Web Goddess. She was quite pleased. She is a Goddess, after all.

JSC: What action would your name be if it were a verb?

IN: It already is. To “pull and Ira” is to engage in awkward, unplanned physical or verbal comedy. I love making my friends laugh, but I will allow that it isn’t always intentional.

JSC: Are there underrepresented groups or ideas featured in your book? If so, discuss them.

IN: Underrepresented groups are sprinkled throughout my writing. The main character in my first novel, Noomi Rapier, is a black woman (based on my best friend and Web Goddess). Part of the reason I created her was to explore how a woman would fit into the male dominated world of Transdimensional Authority investigators.

I introduce a lesbian, Radames Trafshanian, in my third novel. In the fourth novel, we find that her organization, the Time Agency, is mostly staffed by lesbians, in part because I wanted to explore a female dominated organization.

A character who runs through my Alternate Reality News Service stories and appears in my fifth novel is Brenda Bruntdland-Govanni, the Editrix-in-Chief. At six foot six, she is very imposing, and she constantly screams and threatens to slap people. I hope she becomes an avatar for female rage, which I see in many of my female friends but rarely see portrayed in works of art.

One of my favourite creations is Syb Goodman, who appears in a TV series I created called The Love Box (which is about a family that lives over and runs the biggest porn store in the world). Syb is completely androgynous; there is no way to determine if they are male or female. The series is an attempt to create a sex-positive show, with a theme that whatever consenting adults do in private is nobody’s business but their own. Syb reminds us that ambiguous sexuality is just as legitimate as overt sexuality. (The aliens in my trilogy all start out without gender, but when they come to Earth Prime, they have to recreate themselves in human bodies, so they take on a gender.)

Because I write a lot of satire, I can’t say that there isn’t a point to creating characters you don’t see as often as you should in popular entertainment: representation matters. But for me, a lot of the fun of writing is exploring people who are not like you, which is a major motivator in my desire to create a diverse set of characters in my work. And while characters can embody ideas, they wouldn’t be very satisfying if that was all there was to them, if the reader/viewer couldn’t relate to them as people. My hope is that they work on all of the levels I have tried to put into them.

JSC: Are you a plotter or a pantser?

IN: Plotter. Before I sit down to write a story, especially a long story like a novel, I need to know the beginning, the end and as many of the points along the way as I will need to get me from one to the other.

I was talking to Paul Levinson once on this subject. He is very much a pantser. When I told him I was a plotter, he asked, “Where does the spontaneity come in?” Well. Knowing that a scene has to have a certain outcome doesn’t change the fact that there are a lot of different ways to build the scene to get it there. There is a lot of spontaneity working within the narrative structures I generate.

It is also worth noting that I write a highly propulsive form of humour, with jokes coming in at the micro level of paragraphs and often sentences as well as the macro level of chapters and the overall story. My writing is constantly playful, which requires a lot of spontaneity at virtually every moment of writing.

JSC: What was your first published work? Tell me a little about it.

IN: When I was growing up, I wanted to be Art Buchwald, the preeminent political satirist of his generation. (My web site, Les Pages aux Folles {http://www.lespagesauxfolles.ca}, was heavily influenced by him, as well as other satirists of the 1950s and 1960s.) From 1984 to 1987, I wrote 300 pieces of satirical fiction that would have fit nicely into a newspaper column.

At the time, I frequently read a magazine called Comic Relief. It reprinted the previous month’s best editorial cartoon and newspaper humour columns. The magazine also had a feature for up-and-coming artists; I decided to submit a few columns and see if they would publish prose as well as comics. To my delight, they did, so my first sale was three articles to Comic Relief. Of course, my pay was a lifetime subscription to the magazine, but I really enjoyed it, and, in any case, the subscription was probably worth more than the handful of dollars that I would have made if they paid in cash.

I was so thrilled that I didn’t sell another story for at least 20 years.

JSC: How did you deal with rejection letters?

IN: Speaking of which…

They say you aren’t a writer until you’ve had at least 100 rejections. By this criterion, I’m a writer at least three times over. And even now, I get far more rejections than I do acceptances. This is the nature of the business. You really have to develop a thick skin, or be so driven that you don’t take the rejections personally. (And, unless the editor says something like, “I hate your story, I hate you and I hate whoever dresses you!”, it really isn’t personal.)

Mostly, I deal with rejection by distraction. My distraction takes two forms. I always have several stories in circulation, so I can console myself with the idea that if one is rejected, perhaps one of the others will be accepted. And I’m always writing. When the rejection comes, I can console myself with how great the current story I am working on is.

JSC: What is the most heartfelt thing a reader has said to you?

IN: At one of the first cons I attended, a woman bought one of the three books I had on my table on Friday. The next day, she came back to the table and said, “I started reading your book last night and loved it. I want to buy everything you have here because I don’t know if I will ever get another chance.”

It’s little things like that that make me think that maybe I haven’t completely wasted my life with this writing thing.

JSC: What were your goals and intentions in this book, and how well do you feel you achieved them?

IN: The book I’m here to talk about is my most recently published novel Good Intentions: The Multiverse Refugees Trilogy: First Pie in the Face. I should mention that as of this writing I have two additional novels awaiting acceptance by my publisher (Elsewhen Press – check out their amazing books at https://elsewhen.press/): Bad Actors: The Multiverse Refugees Trilogy: Second Seltzer Shpritz Down the Pants, the second book in the trilogy, and Fraidy’s Amazeballs ARggles Adventure, a book which wasn’t conceived as part of the trilogy, but which nestles comfortably between the first two volumes. I’m writing this interview well in advance of its publication, so one of those books may be out by the time you read this.

My novels take place in a world where travel between dimensions is possible, but highly regulated; in the first novel (Welcome to the Multiverse*), we find out what happens when people are allowed to travel willy-nilly between universes. It’s ugly with a capital UGH. So, there is an organization called the Transdimensional Authority which monitors and polices travel between realities. If you’re somewhere you shouldn’t be, doing something naughty, their investigators are the ones who find you, stop you and take you back to where you belong.

At the end of the second novel in the series (You Can’t Kill the Multiverse*), a madman sets in motion a machine that he hopes will destroy all of the universes. It doesn’t appear to do anything. Just to be on the safe side, Doctor Alhambra, the chief scientist of the Transdimensional Authority, creates a device that will monitor the known universes for signs of decay.

At the beginning of Good Intentions, the alarm goes off.

The novel is about how politics leads the Transdimensional Authority to develop an ambitious plan to relocate all of the 17 (or 19 or 24 – the aliens weren’t all that concerned with taking censuses) billion sentient beings from that universe to stable universes. It depicts first contact with the aliens, and shows the first alien immigrating to Earth Prime.

My goal with the book is, as with all of my books, to have a lot of fun. My theory is that if I have fun writing it, that will translate to the reader having fun reading it. I succeeded on my end; I hope readers will get the same level of joy out of it.

Specifically, Good Intentions was intended to introduce readers to the relocation programme and the alien species, which is the ultimate group of tricksters. It depicts a generally positive immigrant experience, although there are a couple of dark clouds towards the end of the novel that hint at how chaotic things are going to become in the next couple of novels in the trilogy.

Overall, I believe that it does exactly what a first novel in a trilogy needs to do.

* Sorry for the Inconvenience

** But You Can Mess With its Head

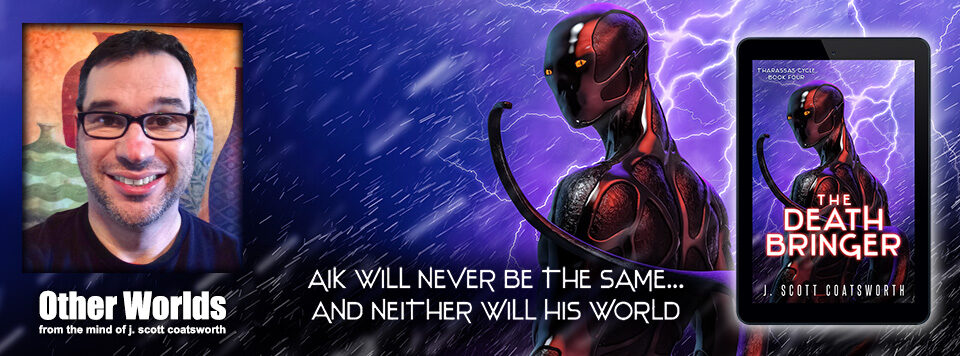

And now for Ira’s latest book: The Multiverse Refugees Trilogy:

At the end of You Can’t Kill the Multiverse (But You Can Mess With its Head), Doctor Alhambra, the chief scientist of the Transdimensional Authority set up an alarm to warn him if a dimension was succumbing to the universe-killing machine that is at the heart of the story. But how would the Transdimensional Authority respond if the alarm went off?

In Good Intentions, the first book in the Multiverse Refugees Trilogy, but also the sixth Transdimensional Authority novel, we find out. In the process, we not only meet the most unusual refugees in fiction (probably), learn what Noomi Rapier’s brother does (and with whom), and revisit Dingle Dell, but finally discover what happened to chapter seventeen of the previous book in the series, The Multiverse is a Nice Place to Visit, But I Wouldn’t Want to Live There.

Reading public, you’re welcome.

Get It On Amazon

Excerpt

The cork from the champagne bottle flew past Hal, the skeleton Doctor Alhambra kept in the Transdimensional Authority’s Lab the Sixth in case he had to explain the difference between a tracheotomy and a vasectomy to a new hire, not Hal, the x-ray (among other things) technician, although, to be fair, the x-ray (among other things) technician could stand to gain a few pounds, ricocheted off Centrifuge C (widely regarded by the scientists who regularly used her as “the least introspective piece of equipment that applies centrifugal force for the sedimentation of heterogeneous mixtures in the entire lab!”), knocked loose a bit of tape holding up a poster on lab safety (whose message consisted of twenty-three different ways of saying that people in the lab should not aim lasers at each other’s eyes), causing it ominously to curl away from the wall, hit the back of the head of eighty-three year-old theoretical alternauticist, James Stubbing-Toews, (who had for several months been working on the theory that he did not need a full night’s sleep, just twenty-three naps during the course of a day) causing him to awaken with a start and say, “I’m innocent, your honour! The chipmunk pate had already dripped onto the painting of the monk Chip’s pate when I got there!” before arcing majestically in the air and coming to rest at the feet of Betty bos Vassant.

“Dammit!” muttered Martin Gilmandrooley, a swarthy xenopsychologist from Bangalore who had read a book by P. G. Wodehouse when he was a child and, as a result, aspired to be an upper class twit when he grew up. “I was aiming for her ample cleavage!”

“Did you factor in the inelasticity of Old Jimbo’s head?” asked Tim ‘The Kit’ Oompaloomp (he hadn’t been given the nickname because he always carried a set of useful tools in his Cars 2 backpack – although he did – or because his angular face and blue eyes made him look like a young fox – which they did – it was because somebody misspelled ‘kilt’ in his high school yearbook – a sartorial affectation that afflicted him in his teens – and he decided to run with it) as he held out a flute (champagne tastes so much better when drunk out of a musical instrument, doesn’t it?) and gestured for the pouring to commence.

Bos Vassant shook her head ruefully. She had done this so often since she had accepted the Transdimensional Authority’s Comfy Chair in Mathematics (a position once held by Sir Isaac Newton) that she had had to hire a personal trainer to strengthen her neck muscles. If you asked her why she dressed in a manner that showed off her ample cleavage, she would reply, “I love my body almost as much as I love solving twelve dimensional trans-universal vector geometry problems…in my head!”

You tell her girly girls can’t be the smartest people in the room!

Doctor Alhambra stood in a corner of the large room, serenely watching the shenanigans of the Transdimensional Authority science division’s annual ChristmaKwaanzUkah shenanig in front of him. Well, serener than the TA’s Chief Scientist usually was. The fact that the 8-bit versions of holiday classics such as “Grandma Got Run Over by a Reindeer” and “Fish Heads” were being blasted on the sound system did not help him maintain his calmness, but he clutched his serenity tightly to his bosom and carried on. The multicoloured lasers bouncing off silver Möbius strips hanging from the wall made for a fair approximation of a disco ball, but the thought of all of the safety posters going for nought added -3 to his serenity level. The burning Hanukkah bush seemed, to him, to be a waste of a perfectly good spectral interferometer, but, after a moment’s disdainful scorn, he shrugged it off as a small price to pay to maintain lab bonpersonneamie.

It wasn’t even that the only belief system Doctor Alhambra recognized as having any form of legitimacy was * SCIENCE *! (Yes, all in caps and including the asterisks – his was a stern belief system that demanded attention and respect.) All-powerful sky beings meant nothing to him unless they arrived on Earth in spaceships and spoke pure mathematics. The fact that some people didn’t share this belief and still called themselves scientists was one of life’s mysteries that defied all of his attempts at rational solution (that and the enduring popularity of Tyler Perry’s Medea movies). Doctor Alhambra didn’t allow even that to significantly affect the cockles of his dourness (he had attached the cockles with chains to make his dour easier to lift and carry).

No, the only thing that made the annual effort at forced fellow- and ladyship, including the Secret Simon the nondenomination embodiment of ChristmaKwaanzUkah gift exchange (this year he got his draw, Melodie in shipping, an app that calculated the direction to Mecca from any point in the galaxy; in return, she knitted him a pair of mismatched socks), less bearable was the fact that he couldn’t drink. Oh, he did drink, everything from Slatonic Rhino Ale to Pandimensional Gargle Blasters (like Pan-galactic Gargle Blasters, but they affect the sobriety of all versions of you within a seven reality radius); it’s just that alcohol had no effect on him. Soon after he joined the Transdimensional Authority, people with Nth degrees started dying under mysterious circumstances. Since there were only seven of them on Earth Prime at the time, Doctor Alhambra thought it best to take precautions. He programmed nanobots to constantly monitor his blood for traces of toxic substances and, if they found anything, no matter how slight, to immediately neutralize it. The good news was that he survived.* The bad news was that the nanobots could not differentiate between bad poisons (strychnine or arsenic) and good poisons (a double whisky on the rocks), forcing the scientist to live through office holiday parties STONE. COLD. SOBER.

* For more information on the incident, see: Neidergaarden, Laurie,

“Too Smart to Live, Too Stupid to Contemplate,” Alternate Reality

News Service (V37, I231, Tuesday).

“Happy snibbler’s giblets!” Doctor Richardson roared, giving Doctor Alhambra a slap on the back that was so hearty you could be forgiven for wondering why Doctor Frankenstein hadn’t gotten Igor to make off with it for his latest creation. The slap on the back was so enthusiastic, in fact, that Doctor Alhambra was immediately inspired to plot some form of revenge. Uhh….I mean, find a new area of science to experiment on Doctor Richardson. With! With – to experiment with Doctor Richardson! In.

Oh, you get the idea.

Assistant Chief Scientist (a position that didn’t actually exist, but made him very proud about owning a t-shirt proclaiming it) Doctor Richardson was the rotund, jovial Transdimensional Authority researcher – his joviality rivalled Doctor Alhambra’s dourality, cancelling each other out and leaving the lab an inspirational management dead zone. Having only multiple PhDs (111 in base two at last count), he was more susceptible to the sins of the flesh.

“You’re drunk!” Doctor Alhambra stated more directly than I just did.

“I am not fullerbrush!” Doctor Richardson responded with the dignity of a small town mayor denying he had borrowed money from the local church’s Windows and Organs fund. “I am pleasantly grobblestudded!”

“Ah,” Doctor Alhambra ahed and took an impotent swig of grog. “You don’t even know you’re doing it, do you?”

“Gotterdammering what?” Doctor Richardson innocently asked.

“Doctor Richardson, I hate to break this to you, but – well, actually, no, hate is too strong a word. Mildly annoyed might be a better way of describing my emotions at this moment. Perhaps mildly is not appropriate, either, but I’m willing to allow historians to debate that question. What I’m trying to say is –” Doctor Alhambra stopped as a small plastic object thwacked him in the forehead. Reflexively, with his free hand he caught the object before it splooshed into his drink. Then, he glared at Jared Elstree and Renaldo Ealing, who were just rising from being hunched over a table hockey game that had been set up on Workstation 12.

“Uhh, sorry about that, Doctor A,” Elstree, the skinny Californian with white hair (despite being only 23) whom somebody must have called the Silver Surfer at some time in his life, a reference he would have not appreciated as the only comics he had ever read were EC horror titles from the 1950s (the issue featuring ‘The Bloody Titmouse’ was his favourite), halfheartedly apologized. “We were just, like, you know, really into the game.”

“Not at all,” Doctor Alhambra graciously replied. “I was rumoured to have been young once, myself.”

“So, bruh,” Ealing, a dark-skinned, curly-black-haired young man whose body was so tense it always looked like it was poised to repel an alien invasion, which made his good cheer seventeen times more forced than that of the average person, “Uhh, sorry, I meant Doctor bruh, you gonna give us our puck back, or wha’?”

“No.”

“No?”

Doctor Alhambra contemplatively played the small object between his thumb and forefinger. “Let me tell you a story…” he began.

Inwardly, Elstree moaned. Inwardly, Ealing urgently whispered, “Bruh! Don’t inwardly moan so loud! You never know what Doctor Bruh can hear!”

Ignoring this subtext in such a pointed way that it pointed out how much effort he was putting into ignoring it, Doctor Alhambra continued: “Between my seventh and fifteenth degrees, table hockey was all the rage at the Nth Academy. We all played it in our spare time. Some students even took an extra year on whatever degree they happened to be working on at the time to get good at the game. Not me, of course. But, some. After a couple of years, we couldn’t help but notice that the puck had gone missing. We assumed that the mice got loose from their cage in the middle of the night and made off with the puck as part of that day’s plan to take over the world. The fact that we never caught a mouse with a puck in its cage did not entirely rule out the possibility, but it did give some of us pause. Some of us. As an alternative, that very same some of us (of which I am proud to be an honourary member, although I may be stretching the term proud a little…past its breaking point) postulated that the mice were addicted to the game, but very bad at it, as a result of which they managed to shoot the puck off the table, down the hall, into the elevator, down several floors, out of the elevator and through a Dimensional PortalTM into another dimension, never to be slap shot by any of us again. No matter. Table hockey pucks are easily replaced. But then the replacements disappeared. Then, the replacements of the replacements disappeared. It got so bad that replacement pucks seemed to vanish the moment we took them out of the package! Well. Reasonable people may have given up the game at that point, but we were not reasonable people – we were scientists! We devised a system whereby we could play the game without pucks using nothing but the power of our minds! In the beginning, disputes were plentiful, I can assure you. Still, we persevered. And in the end, we triumphed. You think you have to focus playing the game the traditional way? Gentlemen, you have no idea what focus is until you’ve won Lord Stanley’s Cup without a puck!”

“Whoa!” Elstree commented, wonder oozing from his voice.

“So, uhh, does this mean that you were, you know, serious when you said you aren’t going to give us the puck back?” Ealing asked.

“I would be doing you a disservice if I did,” Doctor Alhambra informed him, pocketing the puck. “I would be depriving you of the opportunity to play the game as it was meant to be played!”

Elstree and Ealing went back to their game. At first, there was much cursing and arguing – so, no difference there. After a couple of minutes, nobody paid any attention to the game’s typical rambunctiousness.

“Your dourness takes all the fun out of a ChristmaKwaanzUkah confritterlistness!” Doctor Richardson groused. If I parsed his syntax correctly.

“I have been told,” Doctor Alhambra acknowledged. Dourly.

“Did you ever find out what happened?” a woman’s voice asked. Bos Vassant had sidled up to Doctor Alhambra’s other, Doctor Richardsonless side.

“What happened?”

“To the missing hockey pucks.”

“Oh. That.” Doctor Alhambra waved a pfffty hand. “It only took me a couple of months to realize that Doctor Smith was using them for target practice for his Personal Laser-based Defence System (PLDS) prototype. The cheap bastard figured he could save the Transdimensional Authority a few bucks by having us replace them. Did I mention that he was a cheap bastard? Still…best quantum poker player I ever had the pleasure of meeting!”

All of the men in the lab under the age of seventy-five were jealous of Doctor Alhambra, whom they assumed was sleeping with bos Vassant. They were correct to the extent that Doctor Alhambra and bos Vassant often slept in the same bed. They were wrong, however, in the implication that because they slept in the same bed that they were actually sleeping together. Sexually, I mean. For Doctor Alhambra and bos Vassant were asexual; their sex drive was so small that there wasn’t a metaphor for tininess in the English language that could do it justice. Mostly, they whispered sweet transdimensional matter/information equations in each other’s ears and drank cocoa until they both fell asleep.

Don’t judge them. They’re probably happier together than you are in your current relationship.

“How you holding up?” bos Vassant asked.

“Peachy as passelfarts!” Doctor Richardson roared.

“Good to know,” bos Vassant took the eruption in stride.

“And you, Doctor Alhambra, how are you holding up?”

“Thank you for asking, Doctor bos Vassant,” Doctor Alhambra unemotionally answered. “On the Larry David Vexation Scale, I’m at approximately two hundred thirty-eight.”

“Well within normal parameters for this time of year, then.”

“Quite.” Doctor Alhambra was about to explain how he could use the table hockey puck as a talisman to channel his most negative responses to the humanity around him (I’ll be honest with you: quantum laser scalpels would be involved), forcing bos Vassant to make a polite comment about it eventually becoming denser than a black hole, when something caught his ear. “Do you hear that?” he asked.

“I chromasticate many flashbubs,” Doctor Richardson thoughtfully stated.

Doctor Alhambra stepped out of the corner and shouted, “Be quiet, everybody!” Waving his arms to get everybody’s attention, he shouted even harder, “Will everybody shut the ferk up!”

Everybody shut the ferk up. The music, however, continued to play, an especially jaunty 8-bit version of “The Dreidel Song” marred only by the fact that it was made up of a mere four lines that were repeated eighty-seven times…and the fact that, yes, another sound…even more repetitive…insistent…urgent interfered with it. “Oh, will somebody please turn that noise – I’m sorry, that religiously celebratory noise off!”

The religiously celebratory noise was turned off.

Beedleboop could be heard. Beedleboop beedleboop beedleboop.

“I can hear it!” Doctor Richardson exulted. “I can krumpf intellifact!”

Doctor Alhambra knew he knew the sound; he had programmed all of the alarms in the building, after all. This one couldn’t have gone off all that often, because what it was trying to warn him of didn’t come immediately to mind. The fire alarm? No, that was more of a ooohunh ooohunh ooohunh. The anti-theft alarm of the Dimensional DeloreanTM? No, that one went oooga oooga awoooga oooga. It may have been the sound of the chaos coffeemaker telling him that his morning tea was ready just the way he liked it…probably…maybe…well, honestly, there are no guarantees in this world, except that that sounded like Scarlett Johansson saying, “Doctor Alhambra, your morning tea is ready just the way you like it…probably…maybe…well, honestly, there are no guarantees in this world…” The particle accelerator alarm was a mellow chew-ba-ca chew-ba-ca chew-ba-ca. And of course, the breached Dimensional PortalTM reality containment field was more of an “Ohmygod! Ohmygod! Ohmygod!” If the alarm wasn’t any of the obvious ones, what could it possibly be trying to warn him of? What could it poss…i…bly…

Doctor Alhambra Blanched (although many of his friends and family advised him that it was a complete waste of time, his MFA in Theatre Arts continued to pay him rich dividends). He also turned very, very white. The reason he hadn’t recognized the alarm was that it had never gone off before. In fact, when he created it, he had hoped that the alarm would never be needed. What it demanded his attention for was very serious. Very, very serious. Very, very, very serious. Very, very, very, very serious. Very, very, very, very, very serious.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is how we cross over into five verys territory…