Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

Today, Gordon Bonnet – Gordon’s love of storytelling goes back a long way—to first grade, in fact, when an assignment to write a story then read it to the class went so wildly well that he swore he was going to tell stories forever.

His interest in the paranormal goes back almost that far. Introduced to speculative, fantasy, and science fiction by such giants in the tradition as Madeleine L’Engle, Lloyd Alexander, Isaac Asimov, C. S. Lewis, and J. R. R. Tolkien, he was captivated by those writers’ abilities to take the reader to a fictional world and make it seem tangible, to breathe life and passion and personality into characters who were (sometimes) not even human. He made journeys into darker realms upon meeting the works of Edgar Allen Poe and H. P. Lovecraft during his teenage years, and those authors still influence his imagination and his writing to this day, as do more recent discoveries like Haruki Murakami and Neil Gaiman.

This fascination with the paranormal, however, has always been tempered by Gordon’s scientific training. This has led to a strange duality; his work as a skeptic and debunker on the popular blog Skeptophilia, while simultaneously writing paranormal and speculative novels, novellas, and short stories. He blogs daily, and is never without a piece of fiction in progress – driven to continue, as he puts it, “because I want to find out how the story ends.”

Gordon currently lives in upstate New York with his wife and two dogs.

Thanks so much, Gordon, for joining me:

J. Scott Coatsworth: How would you describe your writing style/genre?

Gordon Bonnet: I write speculative fiction. I would describe it as taking the world and tweaking some of the rules, and seeing what happens. What if you could keep track of all the possible decisions you could have made… and see their consequences? What if all the lost items in the world have side-slipped into what amounts to the universal junkyard? What would it really be like to be telepathic, 24/7? What if the things you see out of the corner of your eye are real, but vanish when you look at them straight on?

I love dropping perfectly ordinary characters into these completely surreal situations, and seeing how they react.

JSC: What was your first published work? Tell me a little about it.

GB: My first published work (in 2015) was my novel Kill Switch. At the time I wrote it I was a high school teacher, and so is the main character, Chris Franzia—although I hasten to add that other than that, he’s not really very much like me. He comes home on the last day of school, ready to start a relaxing summer, to find there are two FBI agents waiting for him. They tell him that in the past month five people have died under mysterious circumstances, and the only link the investigators can find between them is that they were all in the same college biology class, thirty years earlier. That—and a highly suggestive email from one of the victims, sent the day before he died—has led the FBI to conclude that someone is systematically killing the people who were in that class. And that Chris is next.

A funny postscript is that a woman came up to me at a book signing and said she’d read Kill Switch, and it became quickly obvious that she thought it was non-fiction—and autobiographical. I quickly told her that Chris Franzia was completely made up, as was every other character in the book, and all the events therein. She kind of wiggled her eyebrows, leaned forward, and said in a quiet voice, “Don’t worry. I can keep a secret.’

JSC: Do you ever base your characters on real people? If so, what are the pitfalls you’ve run into doing so?

GB: Like all writers, I collect characters. All of my characters have traits that come from somewhere, mostly from people I know. But there are only two cases where I based entire characters on friends and acquaintances. The first one is the Chief of Police’s loony, dope-smoking mother in Signal to Noise, and in the interest of keeping the peace I probably shouldn’t mention who she’s based on. (But if you read it, and you think, “C’mon, no one is this over-the-top nuts”… all I can say is that whole pieces of dialogue are lifted from conversations with this woman.)

This brings up the pitfall, which of course is “What if she reads the book and recognizes herself?” I can say with confidence that the likelihood of her reading my books is slim to none, and even if she did, she’s not exactly what I’d call “self-aware.” So I think I’m safe.

The other example, which was enormous fun to write, is Slings & Arrows, the seventh in my Snowe Agency murder mystery series. It was written as an hommage to my dear friends in the online writers’ group The Quillies, and was done with their permission (and full approval). All of the suspects are based on one of the Quillies, right down to appearance and first name.

JSC: Do you read your book reviews? How do you deal with bad or good ones?

GB: I never read reviews unless someone sends one to me. (Which happens very rarely.) My attitude is that reviews are for readers, not writers, and a bad review probably wouldn’t change my writing, so what’s the point?

Also, I’m pretty emotional and sensitive, and my writing is extremely important to me. I know about myself that one bad review would bring me down more than a hundred good ones would bring me up, so it’s not worth it.

JSC: Are there underrepresented groups or ideas featured if your book? If so, discuss them.

GB: I try to write so that my stories’ characters reflect the reality of people in the world, and to do it in an authentic way. In other words, so that characters who aren’t part of the privileged, over-represented wealthy straight white Americans demographic aren’t just tokens. Most of the time this happens organically as the story develops. My characters usually come to me with all their personality characteristics already there, so it’s not like I take a character and say, “Hey, I know, I’ll make him gay!”

To me, it’s a really interesting challenge to write from the POV of a character who is really different than I am—one example that comes to mind immediately is Lissa George, the brilliant and insightful physicist in The Fifth Day. Lissa is a person of color from Belize, and is a lesbian.

My current work in progress has several characters from underrepresented groups—college professor Soren Conover (who is gay), artist Brandon Nguyen (Vietnamese-American), retired nurse Julia Lowell (African-American), and the deep, thoughtful five-year-old Perry Abraham (who is autistic). Each of these has given me the chance to explore what the world would be like through different eyes than my own.

As an aside, anyone who is considering taking on the challenge of writing from a different POV should read the wonderful book by Nisi Shawl and Cynthia Ward called Writing the Other. It gives excellent, down-to-earth advice to writers about creating authentic characters who aren’t simply reflections of the author’s own demographics. It’s a must-read, and is available at Amazon.

JSC: Do your books spring to life from a character first or an idea?

GB: It’s almost always from an idea or an image so compelling that I have to write the story to find out its significance. The most striking example of that I can think of is my short story “Retrograde,” which came from an image of a young man going into a café on a cold, snowy night, and as soon as the woman at the counter—someone he has never seen before in his life—sees him walk in, she starts to cry.

Why on earth would this happen? And what connection that powerful could possibly exist between two total strangers? It took writing the entire story to answer that.

Another example is my short story “The Sugar Mill,” which is based upon a ruined building I saw when I was visiting Belize on a birdwatching trip with my wife. It’s an abandoned nineteenth-century sugar mill, and is one of the single eeriest places I’ve ever seen. When I saw it, the thought came from nowhere: “It’s haunted, but the ghost doesn’t just scare you, it alters who you are.” Naturally I had to find out what that was all about.

JSC: Name the book you like most among all you’ve written, and tell us why.

GB: It’s my novel Sephirot. The story itself had been percolating in my brain ever since I was about twenty and stumbled upon the Jewish mystical tradition of that name, which speaks of ten interlocked worlds that represent the movement of the mind on the path to enlightenment. And I thought, “What if it wasn’t a metaphor? What if these were real worlds someone had to navigate his way through?”

It seemed like such a huge undertaking that I kept making excuses to work on other projects, but in about 2015 (so 35 years after I first got the idea) I launched into the story of Duncan Kyle and his adventures while trapped in the worlds of the Sephirot. Perhaps because I let it stew so long, it really felt like I was pouring a part of my heart onto the page, and it’s still the story I feel the closest to.

JSC: What is the most heartfelt thing a reader has said to you?

GB: It was when one of my editors, Gil Miller—who is himself a writer—told me that when he got to the end of Sephirot, it made him cry. Gil, who since working as my editor has developed into a close friend, is a tough, gruff ex-military man who would be high on the list of people you’d never expect to cry over a novel. But mine got him. He said, “The ending of that book is one of the most deeply moving things I’ve ever read. I spent most of the book thinking, ‘How is he going to manage to wrap this up?”, and after I read the last page I realized that was the only possible way it could have ended.”

JSC: Tell me one thing hardly anyone knows about you.

GB: Well, my family and close friends know that I have prosopagnosia, better known as “face blindness.” I form no mental images of faces at all. If I recognize someone, it will be either be because of a distinctive feature—he’s the guy with the curly gray hair and black plastic-framed glasses, she’s the woman with hair dyed blue who wears a stud in one nostril—or from something else, like voice or posture. It backfires, of course, when someone changes their appearance, like my former student who showed up on the first day of class, sat down in the front row and said hi, and I said, “Hi, I’m Mr. Bonnet, what’s your name?” She looked at me like I’d lost my mind, and said, “Same as it was last year, when I sat in this same seat in your intro biology class.” During the summer she’d cut her hair really short, and I honestly didn’t recognize her at all.

The truth is I don’t have a mental image of my own face. I know my features—long sandy blond hair, narrow face, a bit of an outsized nose—but it doesn’t come together into any kind of picture. (An acquaintance who found out about this odd disability said, “You mean… when you look at yourself in the bathroom mirror, you don’t know it’s you?” I responded, “Of course I know it’s me. I’m the only one in the bathroom. I’m face-blind, not stupid.”)

I was able to turn this to one benefit, though—the third of my Snowe Agency mysteries, Face Value, is about a man who is face-blind, and is the only witness to a murder. He can’t identify the murderer, of course, but the murderer doesn’t know that—so in short order he becomes a target.

JSC: Which of your own characters would you Kill? Fuck? Marry? And why?

GB: Now there’s a question I’ve never been asked before! Kill? The character of Lydia Moreton in my work-in-progress, In the Midst of Lions. That woman is pure distilled evil. Fuck? Well, I’m bisexual, so I get two. Bethany Hale from my Snowe Agency series is brilliant, funny, and smokin’ hot. Doctor Will Daigle from Whistling in the Dark is not only gorgeous and smart, he’s also queer, so I might have a shot with him. Marry? There are a lot of them who are pretty cool and might make great potential spouses, but I probably should end here. I’m already gonna be in enough trouble with my wife over the “fuck” part of this question.

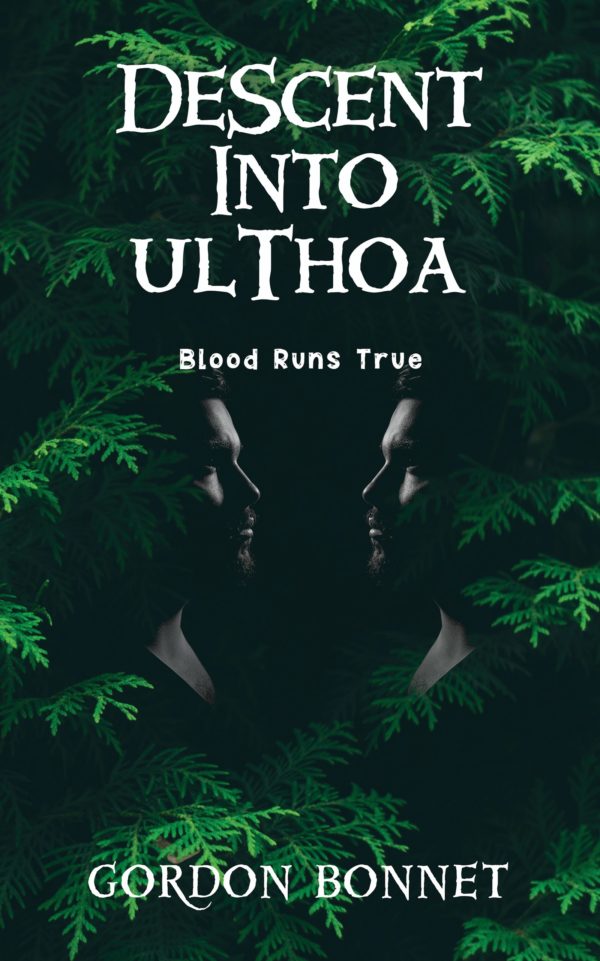

And now for Gordon’s latest book: Descent Into Ulthoa:

Ten years ago, a man and his girlfriend went into the woods at the end of Claver Road on what was supposed to be a weekend’s camping trip, and never returned. Police combed the area, but nothing was found except for his car, abandoned where they’d parked it. It seemed like Brad Ellicott and Cara Marshall had been swallowed by the silent, brooding forest, leaving not a trace of what had happened or where they went.

His identical twin brother, left to mourn his loss, has spent the last decade unable to let go of his grief, to accept that Brad and Cara are gone forever. Based on sinister hints from a few of the older residents of Guildford, New York, the closest village to the woods, he discovers that there might be more to the story than the disappearance of a couple of hikers. The woods has had an evil reputation for well over a century, and his brother and his girlfriend are not the first people to defy the warnings and brave the shadows under the trees-nor the first to vanish there.

Becoming obsessed with discovering what happened to his brother, he delves deeper and deeper into the mystery that lies beyond the end of Claver Road, and he uncovers a terrifying truth that challenges everything he believes. Is the knowledge worth the cost? And will he get the answers he needs before the forest claims him as its next victim?

Get It On Amazon

Excerpt

Claver Road doesn’t end. It withers away. First from potholed asphalt to dirt, then to a pair of parallel wheel-ruts, finally fading into a tangle of blackberry, osier, and scrub willow. If you tried following it any farther, you’d soon find yourself lost in the deep forest. There, the only paths are deer trails, and those are few in number. Even the animals shun those woods. The whole place is sunk in silence, stillness, and shadow, where a whisper sounds like a shout, and most humans foolish enough to go that far make sure to leave before nightfall.

Where the deep forest starts is only fifteen miles from the nearest town, the quaint, picture-postcard village of Guildford, New York, but most of Guildford’s residents either don’t know about the place’s reputation or else pretend not to. It shows up on maps as a blank spot, crossed by no roads, inhabited by no one. The eighty-thousand acre tract of woods is nominally owned by New York State, but they don’t manage it, lease it for hunting or grazing, or even post signs at the boundaries. It’s not off limits to hikers and skiers, but the tacit message is clear.

Enter here, and you’re on your own.