Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

Today, Dusk Peterson – Honored in the Rainbow Awards, Dusk Peterson writes historical adventure tales that are speculative fiction: alternate history, historical fantasy, and retrofuture science fiction, including lgbtq novels and young adult fiction. Friendship, family affection, faithful service, and romance often occur in the stories. A resident of Maryland, Mx. Peterson lives with an apprentice and several thousand books.

Thanks so much, Dusk, for joining me!

J. Scott Coatsworth: When did you know you wanted to write, and when did you discover that you were good at it?

Dusk Peterson: I was eight years old when I began writing for my own enjoyment, nine when I decided I’d become a writer (my father is a literary historian and my mother was an amateur reporter and poet, so this decision was a no-brainer), ten or eleven when I read Jacqueline Jackson’s Turn Not Pale, Beloved Snail: A Book About Writing, Among Other Things and began to take concrete steps to become a professional writer, and thirty-two when I finally wrote something that was publishable. Fortunately I’m patient, where writing is concerned.

Being an egotistical child, I never doubted that the stories I wrote were good. Nor did I doubt this as a hypomanic adult. It wasn’t until quite recently that it occurred to me that it might be helpful to get some outside confirmation of my worth as a writer. Fortunately, by that time I’d acquired a few literary awards, and more importantly, a couple of readers had named their pets after my characters. I figured that was a good sign.

JSC: How would you describe your writing style/genre?

DP: How I describe my genre depends on which genre of readership I’m addressing. I’m multi-genre: I write speculative fiction, historical stories, adventure/crime/suspense, war tales, maritime tales, romance, gay/bi fiction, asexual fiction, and queergender fiction. My bookstore categories on any given story are legion.

To speculative fiction readers, I’ll say that I write historical speculative fiction: alternate history, historical fantasy, and retrofuture science fiction.

Most of my stories exist within my Turn-of-the-Century Toughs cycle: Young Toughs, Waterman, Life Prison, Commando, Michael’s House, The Eternal Dungeon, and Dark Light. These series are placed in an alternative version of America between 1880 and 1912 that was settled by inhabitants of the Old World in ancient times. As a result, the New World retains certain classical and medieval custom. Young Toughs and Waterman also dip into a retrofuturistic version of the 1960s.

By contrast, The Great Peninsula (consisting of two series: Young Spies and The Three Lands) is a fantasy cycle, loosely inspired by conflicts between nations during the late Roman Era and Dark Ages.

To gay fiction readers, I’ll say that I often (though not invariably) write what my fellow writer Remy Hart termed powerfic: stories that focus on people of different status or rank. Sometimes the people are in bonds of affection with each other, sometimes they’re in conflict, and often both. (I like drama.) Among other things, I’ve written three series set in wartime, two series set in prisons, and one series set in both wartime and a prison.

To everyone, I’ll say that my goal – whether I’m writing adventure fiction or quiet domestic fiction – is to place characters in a dark situation, and then to have them triumph over that darkness in some manner.

JSC: What was your first published work? Tell me a little about it.

DP: It depends on what you mean by published work. I was a journalist, history writer, e-zine publisher, and online fiction writer during the quarter century before my first e-book appeared.

My first fiction e-book (published in 2007) was also one of my earliest online stories (posted in 2002): Bard of Pain, in the Three Lands series. The blurb has my favorite tagline: “In the battle-weary lands of the Great Peninsula, only one fate is worse than being taken prisoner by the Lieutenant: being taken prisoner if you are the Lieutenant.” The novella is about a notorious wartime torturer who becomes a prisoner of the enemy. He’s placed in the hands of a young torturer who considers the Lieutenant his hero, but that’s not about to stop the young torturer from carrying out his profession.

The story has a mentor-protegé plotline, as well as romantic friendship subplots involving other characters, but it’s not really gay fiction. The rest of the ongoing Three Lands series will include a few LGBTQ characters, and the main character of the series is considered third gender by his society (though not by himself). The primary focus of the series is on committed bonds of friendship.

My first e-book of gay fiction was published in 2008: The New Boy, in the Michael’s House series. It’s set in a 1910s house of prostitution, and it required some of the most difficult research I’ve ever done, because so little information is available on male prostitution during that era. I originally wrote the first two stories in that series for MAS-Zine, an original-slash CD-zine that served as an early m/m romance e-zine; it premiered in 2002. The editor of MAS-Zine, Anne Blue, was kind enough to publish my Michael’s House stories, even though the two main characters in the series are in what I could best term as a romantic friendship.

You can gather from this that I tend to mix-and-match gay and non-gay plotlines in my series.

JSC: What’s your writing process?

DP: My writing process is very much a work in progress. In the old days (that is to say, between age eight and a few years ago), writing was simple: I daydreamed a story about a zillion times, and then, when I got a spare moment, I wrote the story down. That was back when I had stories going through my head 24/7.

These days, I actually have to sit myself down and deliberately think out the story. This being the case, I’m much more likely to have an intermediary stage where I sketch a rough outline of what’s in my head. Here is a typical process for a novelette:

I come up with a concept for a story.

I do historical research. This is great fun and gives me lots of ideas for the storyline. When the ideas start overwhelming the research, it’s time to switch to writing the story.

Now comes the really fun part. I write the story in my head, scene by scene, but not necessarily in chronological order. As it begins to become obvious what order the scenes are in, I’ll jot down a list of the scenes I’ve drafted, which will help me identify which necessary scenes are still missing.

After I’ve written a scene in my head, I write down, either by hand or by typing, what I call the “script”: the dialogue and stage directions, which is all that I have available at that stage. (The story initially comes to me in dialogue and vague visuals. The longer descriptions and the expository passages I insert at the stage when I’m composing the full story.) I don’t always script scenes, but the advantage to doing so is that it allows me to devote more attention in the next stage to writing carefully.

I write the scene. (That is, I type it. For years, WordPerfect was my word processor of choice, but these days I’m beginning to switch over to plain text, using NoteTab if I’m on my laptop or UpWord if I’m on my iPhone and Bluetooth keyboard.) If I’m not sure about a word or a fact, I put brackets in that part of the scene.

As I continue to write the story (or immediately after the story is finished), I lightly edit the scenes by rereading them and tweaking the sentences as I go, usually lightly editing each scene at least twice. In the case of novels and novellas, which I’ll likely write over many months, I do lots of light-editing drafts. As I lightly edit, I add more brackets as needed. This stage is also fun; it’s the closest I can get during the editing to simply being a reader of my own stories.

After I’ve finished the above stages, I edit the story by ear: I e-mail the story to myself and have the text-to-speech software on my iPhone read the story aloud. I can usually catch typos and stylistic awkwardnesses this way. I put in more brackets if I encounter anything that needs to be checked in greater depth.

At this point, my story is top-heavy with brackets, so I tackle them. I go onto the web (this is the first time during the post-research story process that I’ve let myself go on the web) and do oodles of fact-checking. I make heavy use of Google Ngrams and Google Books to identify and eliminate anachronistic words, I pore through my dictionary (Merriam-Webster’s) and style manual (also Merriam-Webster’s), I seek historical facts (this is the second half of my historical research), and I do any other needed hunting.

Once that’s done, I run my story through editing software. At this stage, I’m specifically interested in knowing whether I’ve unintentionally repeated words or phrases. The editing software I use, Pro Writing Aid, has a couple of helpful categories that will tell me if this has happened.

Then comes what I call the “final editing,” which requires me to question every single word and sentence and paragraph in the story, in order to check whether everything’s the way I want it. This usually ends with me going back on the web to check facts online.

As the last step, I do a grammarcheck/spellcheck in hypervigilant Microsoft Word. I’ve been a copy editor since my teens, so with luck, I’ve caught all typos during the previous editing stages, but occasionally something will slip through that the grammarcheck/spellcheck correctly identifies.

It takes me three times longer to edit my stories than to write them, but I think the end result is worth it.

JSC: Tell me one thing hardly anyone knows about you.

DP: I’m visually impaired. This is by no means a secret, but it isn’t a topic that comes up often in my blog, so I imagine a lot of my newer readers don’t know this. Thanks to medical help, my eyes are much, much better than they were in the early 2000s, when I would periodically lose the ability to read with my eyes. (I try to keep up my skills with braille, just in case my eyes ever regress on me.) Even with improved eyesight, though, I still do the majority of my reading and writing in very large type, 20 point to 40 point, depending on the time of year. If it weren’t for computers, my life as a writer would be tough.

Not being able to read print whenever I want does have its inconveniences, of course. On the other hand, a lot of the technology I use today as an author, such as text-to-speech and auto-scrolling and scanners, I began using in the early years of the millennium, before that technology became mainstream, because my diminished eyesight left me with no choice but to seek technological alternatives. More importantly, most of my fiction series began as online fiction series, and I began reading online fiction because I had very little access in those days to any other type of reading matter. (At the beginning of this century, frighteningly few professionally published speculative fiction novels were available in formats that visually impaired people could access.) If I hadn’t been an online fiction writer during the early 00s, then I wouldn’t have had either the content or the technical know-how to begin self-publishing e-books in 2007.

So because I’m partially sighted, I’m much more of a geek today than I would otherwise have been.

JSC: Do you write more on the romance side, or the speculative fiction side? Or both? And why?

DP: Virtually all my stories are about love, but romance is only one of many types of love that I write about. I’m especially interested in stories about romantic friendship (I prefer the term classical friendship) – that is, a committed bond based on love that isn’t sexual. I’ve also written a lot about asexual love, group comradery, nonsexual love between brothers, and the strong affection that can develop between men being served and the men who serve them, whether their love is based on sexual attraction or not. All types of affectionate relationships interest me.

The fact that there is no Friendship genre, the way there is a Romance genre, is a continual trial to me, both as a writer and as a reader. Romance novel blurbs indicate straight away what the romance plotline is, but if I want to find a novel about friendship to read, I have to stick with genres where friendship is a common plotline, such as military fiction or children’s fiction, because the average novel blurb says little or nothing about any friendship plotlines.

As for speculative fiction, writing that genre just comes naturally to me. I’ve written a few works of realistic fiction, but I had to work hard to keep the speculative elements out. Since the time I was a child, I envisioned most of my stories as taking place in alternative worlds that were like our world, but with differences.

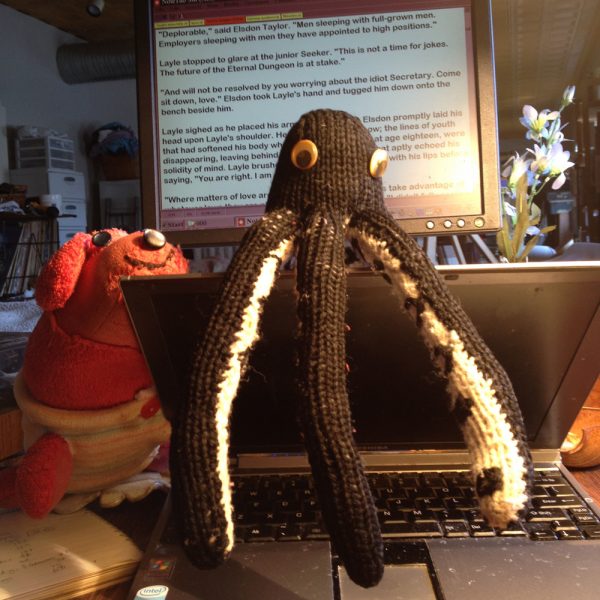

JSC: What pets are currently on your keyboard, and what are their names? Pictures?

DP: Julian is my octopus. He’s named after the emperor. I first met him during college at a children’s bookstore, where he was working as a display; he kindly consented to come home with me. (His creator gave her consent also.) I used to take him to class with me. (College instructor sitting at the head of our discussion table: “And so Mendel hybridized the green peas with the white peas and got— There’s an octopus on the table.”) These days, Julian sleeps with me.

Wiggletail would sleep with us too, but he’s getting rather old; he was a handmade gift from my great-grandmother when I was four years old, to replace a stuffed dog that I’d lost, with bitter tears, at a religious camp meeting our family was attending. My great-grandmother also sent my mother the design and material for making another dog, should I ever lose Wiggletail. The material came in handy during college when Wiggletail needed a skin graft.

Because he’s too frail to sleep with us, Wiggletail sits by the bed and keeps guard over Julian and me. He does a good job at it. No one has ever attacked us at night.

JSC: Are you a plotter or a pantster?

DP: I think the fact that I initially draft stories in my head puts me firmly in the category of pantster. Stories simply play in my head like a movie. However, plotting plays a role after I’ve begun drafting scenes in my head.

JSC: If you could create a new holiday, what would it be?

DP: You’re asking the right person; holidays have been my obsession since I was young. I’m probably one of the few adults who regrets no longer having a schoolteacher who hands out construction paper to make valentines.

The United States of America has had a real problem with holidays, from the time the New World was first settled by Europeans. About half the English colonies in the United States wanted nothing to do with holy days, because the people in those colonies considered holy days to be against their beliefs. The other half of the English colonies did their best to impose their holy days on people who didn’t want to celebrate those holy days.

We’ve been struggling with the problem ever since then. The separation of Church and State didn’t fully resolve the problem; neither did the introduction of national, secular holidays. The best that can be said is that we Americans continue to try to resolve the problem, as best we can.

At the moment, there’s a hole in the national calendar, where spring holidays used to be. Egg hunts and chocolate bunnies are very pale reminders of the sort of joyous revels that used to greet spring. I’m not at all sure whether, in the digital age, it’s even possible to get Americans excited about the arrival of spring, but I’d like to see a nationally celebrated spring holiday take its place alongside Independence Day picnics and Thanksgiving feasts and various midwinter holidays.

JSC: What are you working on now, and when can we expect it?

DP: Since the beginning of the year I’ve brought out eight e-books and reissued thirteen e-books, while my Current Projects list consist of fifty-plus stories. So I’m going to have to word my response with care.

I’m in the process of wrapping up my Eternal Dungeon series, which I began in 2002, and which will wind up being six volumes long, not counting the numerous side stories. It’s going to be about 600,000 words long, again not counting the side stories. This summer I hope to publish Truth and Trust, the last story in the main plotline. In the meantime, I just brought out an updated edition of the series omnibus.

The series, which is set in the alternative America that I mentioned before, is about a nineteenth-century royal prison whose altruistic workers (Seekers) wish to place the best interests of the prisoners first. Unfortunately, the prison’s long-standing custom is to torture prisoners for information on their crimes. As time goes on, this creates more and more tension between the Seekers, who disagree on the best way to transform the hearts of criminals.

The series centers on the relationship between the High Seeker and his love-mate, a fellow Seeker, who find themselves on opposing sides in the conflict. However, there’s a great deal more to the storyline than gay romance: there’s friendship, an asexual character, a queergender character, the close bond between Seeker and guard, the comradeship of commoners against the elite, a rivalry between prisons in warring nations, ethical dilemmas in how to handle particular prisoners, spiritual concerns, the development of the science of psychology, and so forth.

And one bit of final news: As I write this, I’m in the process of placing most of my e-books in Kindle Unlimited (although the Eternal Dungeon series will remain in multiformat for now). I hope that this will make it easier for some readers to gain access to my stories.

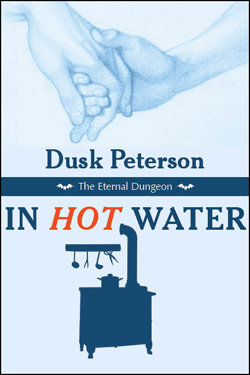

And now for Dusk’s latest book: In Hot Water (The Eternal Dungeon):

And now for Dusk’s latest book: In Hot Water (The Eternal Dungeon):

“He was the flame, and his love-mate was the kindling. To say they were mismatched was an understatement. He knew that it was only a matter of time before their relationship was tested. . . . Layle had simply not expected the test to be a pile of dirty dishes.”

They are two of the most talented prison-workers in the world. It’s a pity their skills don’t extend to dishwashing.

When the kitchen laborers of the queendom’s royal prison refuse to clean dishes until their demands are met, the High Seeker and his love-mate must figure out how to accomplish simple housework that elite men such as themselves never condescend to do. It seems an easy enough task. But hidden between the two men lie memories and secrets that will turn a simple task into something much more.

This romantic short story can be read on its own or as a side story in The Eternal Dungeon, an award-winning speculative fiction series set in a nineteenth-century prison.

The Eternal Dungeon series is part of Turn-of-the-Century Toughs, a cycle of alternate history series (Young Toughs, Waterman, Life Prison, Commando, Michael’s House, The Eternal Dungeon, and Dark Light) about adults and youths on the margins of society, and the people who love them. Set in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the novels and stories take place in an alternative version of America that was settled by inhabitants of the Old World in ancient times. As a result, the New World retains certain classical and medieval customs.

Excerpt

He was the flame, and his love-mate was the kindling. To say they were mismatched was an understatement. He knew that it was only a matter of time before their relationship was tested.

Layle had simply not expected the test to be a pile of dirty dishes.

They both stared at the heap of plates, saucers, cups, glasses, and silverware that were covered with congealed food. The heap represented their meals during the past two days, as both Layle Smith and Elsdon Taylor had bolted food in between questioning their prisoner in one of the breaking cells of the Eternal Dungeon. The heap of dishes lay on the floor in the middle of their sitting room.

Layle was not used to seeing dirty dishes in his living quarters – his “living cell,” in the dungeon parlance. Dirty dishes – like dirty towels, dirty clothes, and anything else filthy – was usually spirited away while he was at his work.

Layle was legally a prisoner within the dungeon and within the small portion of the palace above that he was permitted to visit. All Seekers were classified as prisoners, so that they would not develop dangerous attitudes of superiority over the prisoners whose souls they sought to transform. Yet Layle, who was High Seeker of the queendom’s royal prison, had the reputation as being the most skilled prison-worker in the world. Elsdon Taylor, who was reaching the end of his period as a Seeker-in-Training, had begun to show his own talent in the breaking cell. Men like them were not expected to clean dishes.

Men like them were not expected to know how to clean dishes.

“Er . . . I don’t suppose you ever learned how to wash dishes, did you?” asked Elsdon in a dubious voice.

Layle switched his gaze over to his younger love-mate. They’d only been together for seven months; Layle was still delving into the complexities of Elsdon. Sometimes Layle suspected that his delving would take a lifetime. Still, Layle would not have expected Elsdon – who was currently questioning an alleged murderer in the calmest of manners – to be intimidated by a pile of kitchenware.

“Didn’t you?” Layle challenged. “You were in charge of running your father’s household.”

“We had servants!” protested Elsdon.

Layle should think so; Elsdon’s lineage could be traced back to the fourth daughter of one of the queendom’s previous monarchs. “But you supervised them.”

“For love of the Code, Layle, I didn’t stand over them in the kitchen while they carried out their duties! My mother did that sometimes, before she died, but—” Breathing heavily now, Elsdon looked at Layle. “What about you? You told me last week that you grew up poor.”

“My parents died when I was young.” Layle frowned; his past was not something he wished to discuss with Elsdon. “After that . . . Well, I was not in any position to observe housework.” He had been living on the streets committing crimes, at first because it was the only manner in which he could obtain food, and then—

He forced his mind back to the present, as though it were a prisoner who had sought to escape. That was the past. There was no reason that he should discuss his past with Elsdon. Layle added, “Dishwashing must be simple. We don’t hire the outer-dungeon laborers for their skill in thinking.”

Elsdon scraped at one of the plates with his fingernail. The food stayed solidly put. “How long is this strike likely to last?”

“It’s not officially a strike.” Layle tried to keep his voice patient, though he had spent much of the morning explaining this fact to everyone, from the dungeon’s Codifier to the Queen herself. The Queen, who had no patience with strikes, had suggested replacing the troublesome dishwashers with young women who knew their proper place. Layle, who understood better than the Queen how difficult it was for commoners to survive in a world of hostile employers, had begged permission to handle the matter in his own fashion. He had come home, expecting to be able to have a couple of hours before bed to deal with the problem—

Only to find himself confronted with this blasted pile of dishes.

“We could leave the dishes till tomorrow,” suggested Elsdon. “Perhaps the strike-that’s-not-a-strike will be resolved by then.”

Layle imagined letting the dishes pile up. Then he imagined all of the Seekers letting their dishes pile up, and what that would mean for the young dishwashers once they returned to work. He shook his head. “We don’t want to put that extra burden of labor upon the dishwashers. They seem to be sensible young women.” They had shown their sensibleness by selecting a male laborer from the outer dungeon to present their petition to the High Seeker. Layle did not think he could have coped with the added burden of an enticing female representative. All females were, by definition, enticing. “They’ve sworn to me that they very much desire to continue working for the Eternal Dungeon, and they’ve shown their faithfulness by volunteering to do other labor in the dungeon while I consider their petition.”

Elsdon picked up the piece of paper from the rough work counter that served as a table for their meals. He frowned as he perused the petition. “‘Modern fixtures in the dungeon’s kitchen—’ That seems a reasonable request.”

To Elsdon, perhaps; Layle had already gathered that Elsdon had a boyish interest in inventions. Layle explained patiently, “There is a reason that the workers in this dungeon use older tools, such as daggers rather than revolvers. It serves to keep us rooted in the traditions of the past, so that we do not forget the time when the Code of Seeking was first created.”

Elsdon glanced toward the slim volume that regulated their lives as Seekers. “But the Code of Seeking was revolutionary for its time, wasn’t it? It required the dungeon’s workers to put the best interests of their prisoners first; that departed from centuries of tradition in prison practice. Even your revision of it broke away from past versions of the Code. I would have thought you would welcome modern inventions into the dungeon.”

Layle wondered whether he should explain to Elsdon how often modern inventions fell apart when Layle came near them. But no, they were straying from the subject at hand. “First we have to deal with these dishes,” he pointed out.

Elsdon sighed and stared again at the plates, saucers, cups, glasses, and silverware. “It can’t be so very hard. All we need is water, surely.”

They both looked toward their bedroom. Sitting upon the night-stand next to the bed was a pitcher of water, fresh from being refilled by a maid while they were at work. Under the pitcher lay a small basin. The living cells of the Seekers contained no wash-stands, much less pumps or faucets. Layle had never seen the point of them; the pitcher and basin supplied water just as well as modern plumbing.

Nor was there any sink in the tiny area of the living cell that Layle referred to as their “kitchen.” Storage bins to house nuts and fruit for snacking during their leisure hours, yes, but why should there be a sink? He and his love-mate didn’t prepare food for themselves.

“We could use the water in the pitcher,” Elsdon suggested.

“And pour it where?” asked Layle, looking around as though he expected a sink to pop up at any moment. “That basin is too small for the plates.”

“There’s our washtub. . . .”

Layle snorted. “I am not going to clean dishes in a tub where we bathe weekly. The kitchen must have some sort of container in which we can wash dishes. We simply need a maid to fetch it for us.”

There was a pointed pause. Even Elsdon, who did not know the details of Layle’s fraught past, was aware by now of Layle’s nervousness around women.

Finally Elsdon said, “I’ll find the maid.”

This was ridiculous. Layle was a Seeker. He dealt daily with prisoners accused of heinous murder and rape. For the Queen’s love, he ought to be able to deal with a giggling girl.

“I’ll do it,” he said grimly in the same manner that he might announce he was about to venture into hell.

Buy Links

Amazon: Click Here

Author Bio

Honored in the Rainbow Awards, Dusk Peterson writes historical adventure tales that are speculative fiction: alternate history, historical fantasy, and retrofuture science fiction, including lgbtq novels and young adult fiction. Friendship, family affection, faithful service, and romance often occur in the stories. A resident of Maryland, Mx. Peterson lives with an apprentice and several thousand books. Visit duskpeterson.com for e-books and free fiction. A portal to Dusk Peterson’s young adult fiction is at ya.duskpeterson.com.