Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

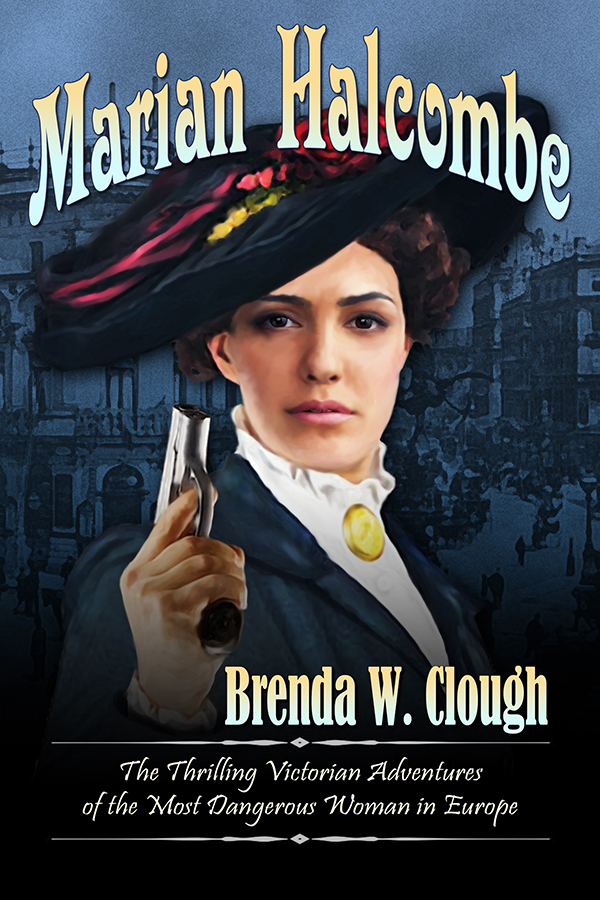

Today: Brenda W. Clough is the first female Asian-American SF writer, first appearing in print in 1984. Her novella ‘May Be Some Time’ was a finalist for both the Hugo and the Nebula awards and became the novel Revise the World. Her latest time travel trilogy is Edge to Center, available at Book View Café. Marian Halcombe, a series of eleven neo-Victorian thrillers appeared in 2021. Her complete bibliography is up on her web page, brendaclough.net

Thanks so much, Brenda, for joining me!

J. Scott Coatsworth: Have you ever taken a trip to research a story? Tell me about it.

Brenda W. Clough: Oh, yes I have! I am writing this while sitting in a holiday rental on the side of a mountain in Italy. I’ve also traveled to France and Britain, all grist for the fiction mill. Google Earth and the travel sites only get you so far. At some point you need to visit a place and not only see it but feel it in your own person – the turn of the seasons, the color of the light, the way the rain falls.

JSC: Do you ever base your characters on real people? If so, what are the pitfalls you’ve run into doing so?

BWC: Perhaps only the physical description – the casting call. Seeing a variety of people helps me to discover what a character looks like. It is important to not just watch TV or movies on this; the universe of actors is a much smaller subset of the human race. Besides, they’ve all had ‘work’ done, plastic surgery. If you sit in a busy restaurant, or an airport waiting area, you really see a cross section of humanity.

The character her or himself, I would scorn to base upon a real person. I have a better imagination than that! By the time I’m done with a book I know the protagonist almost better than I know myself: his psychological weaknesses, his digestion, his sexual proclivities, his choice of cocktails or poetry or car. There’s no point in prying all this detail out of another person even if they would put up with it. If I make all this stuff up, I can adjust everything to fit the work. It’s the same reason why it’s easier to make up a country to set the work in. Then I don’t have to spend days mugging up the history of Moldavia, or whatever. I can create history and incident to suit my needs.

JSC: Do you read your book reviews? How do you deal with bad or good ones?

BWC: Never. Broadway actors never read the reviews while the show is running. It puts them off their performance. But I only fairly recently ran across a glowing review for HOW LIKE A GOD, written by Joe Mayhew. He passed away some years ago, and now it’s too late to thank him for it.

JSC: How long on average does it take you to write a book?

BWC: The first draft can be very fast. I have written 120k in a mere six weeks. But that’s only the first draft. It’s important to rewrite, hone the entire work and hammer it until it’s perfect. This can take another half year or so. I have no difficulty writing a novel a year. It’s why independent publishing is better for me; a traditional publisher just doesn’t keep up. In 2021 I exceeded myself, and wrote three full length novels. I am trying to dial back this year.

JSC: How long have you been writing?

BWC: My first novel, THE CRYSTAL CROWN, came out in 1984 from DAW Books. It was the first full length manuscript I ever completed, and Donald Wollheim was the first publisher I sent it to.

JSC: Are you a plotter or a pantser?

BWC: Oh, I am deeply on the pants side of the force. Outlining is brutal and I never do it. On one occasion I had to write from an outline supplied by someone else. It was like dragging cinder blocks uphill. I far prefer to fly unplanned. Just step up to the edge of the cliff and jump. I never hit bottom. Long before I get there the wings sprout and the story bears me up, and we soar away down the valley of the plot, fast.

JSC: Do your books spring to life from a character first or an idea?

BWC: I like to have an idea. I wrote the EDGE TO CENTER trilogy because I was thinking about how a Victorian gentleman would envision time travel. You need a metaphor. How would he think of it? The notion of a dividers, the tools you use to measure distances on a map, instantly came to mind. And away we go!

I was finishing the eleventh Marian novel, THE COBRA MARKED KING, and towards the end there was one word. The moment I wrote it (actually it was two words, ‘pine cone’) I could feel it. I could put my finger onto the computer screen and when I touched that word it was loose. I knew that if I picked at the edge with my fingernail that word would pop up. And underneath would be an entire different novel. So I had to write it – it’ll be titled A DOOR IN HIS HEAD.

JSC: What were your goals and intentions in Marian Halcombe, and how well do you feel you achieved them?

BWC: I wanted MARIAN HALCOMBE to be a classic Victorian thriller. The work it is based on is THE WOMAN IN WHITE by Wilkie Collins, published in 1860. It’s a classic sensational novel, un-put-downable. I wanted to do that: to hit every trope and expectation of a novel of the period at speed. These books have bigamy, imprisonments, attacks by eagles, combat hippos and snakes, diving for Mayan treasure, sliding over a waterfall in an underground river, identical princes of obscure Balkan nations, amnesia in vast country houses in the English countryside, Jack the Ripper, lost heirs to the throne incognito at Eton and restored to their nation, secret tokens hidden at the back of oil paintings – everything! By the time I got to #11 I thought I was running out of things to do, but little did I know.

JSC: As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

BWC: I remember a party that my parents had, at our house in the Washington DC suburbs. All the adults were upstairs drinking cocktails, and we kids holed up in the basement to watch cartoons. I believe I must have been 13 or 14. A friend of my parents came downstairs to see us, pinching our cheeks and exclaiming how much we had grown. Then she said, “And what are you going to be when you grow up?” I immediately said, “I’m going to write novels.” She was astounded, and went back upstairs, and I promptly forgot the entire incident. Many years later I was in the DC Metro system, riding the train to work, and ran into her. I didn’t remember her name or her face, but she remembered me. She recounted this entire anecdote, the only record I have of it. And I said, “I do write novels, under my married name.” At that moment the doors dinged and opened, and she had to dash out as I called the spelling out after her.

JSC: What are you working on now, and what’s coming out next? Tell us about it!

BWC: I wrote eleven Victorian thrillers about Miss Marian Halcombe very fast, in about seven years. They all came out, one a month, in 2021. And right away the grumbling started. Why aren’t there more? Eleven is a really bad number, you can’t combine them into trilogies or sets. Twelve is really a better number, easily divisible into trilogies or sets of four or six.

And it did occur to me that there are things I should have wedged in. Why, since the books are set in the late 1800s, do none of the characters ever meet Queen Victoria? Neil Gaiman is on record (in an interview in the Guardian newspaper) that spontaneous human combustion is one of the best reasons to read BLEAK HOUSE by Charles Dickens. I’ve put endless creative mayhem into these books, attacks by eagles, trekking through the Central American jungle to dive into cenotes for Mayan gold, arsenic in tea cakes. But I haven’t set anyone mysteriously on fire! And readers are nearly unanimous that there should be more sexy Asian pirates. I could do that.

So I’m writing a 12th Marian which has no title yet.

And now for Brenda’s new book: Marian Halcomb:

The redoubtable Marian Halcombe first burst onto the world in the 1860s in THE WOMAN IN WHITE. Refusing to rest on her laurels, she goes on a life of love and adventure in pure Victorian style.

Bookview Cafe | Amazon

Excerpt

I opened the front door and stepped out. Though it was January we were in the midst of a welcome warm spell. There was no snow nor even frost, and a mild moisture hung in the air, the harbinger of spring. The cottage is divided from the lane by a hornbeam hedge. The bright moonlight lured me down the path to the gate.

I leaned on it and took a deep breath. The pasture and woodland of the Heath were black against a glowing golden haze: the gaslights of London. Warm white mist gathered in the low spots of the landscape, and above in a clement sky the moon was nearly full, modestly veiled in pale ravelings. All was still, not a rustle of leaf or twitter of any bird. It was a calm silent night of the full moon just like this, when Walter encountered Anne Catherick on his walk home, not so far from this very spot. What a fateful encounter that had been for all of us! How many lives and deaths had turned upon that one chance meeting! Surely the finger of God was upon Walter that day –

My rather melodramatic reminiscences were abruptly broken off. There was something stirring, moving purposefully in the mist cupped down the slope. For a moment I wanted to retreat into the cottage and bolt the door. But then I schooled myself to wait and watch. What boggart or villain could there be, here in this quiet suburb? It might only be Sarah, returning from the sewing meeting. How silly I should feel, if she had to knock on her own door to be let in.

So I watched as the mist thickened and then thinned again, and suddenly I could clearly discern two small figures, hand in hand. Could they be children, out alone at this late hour? They wandered nearer, up the lane. I could see they were a fair boy and a quite little girl, perhaps seven and five years old, clad in coats over their nightshirts. Innocent of socks or stockings, their little feet were crammed into untidily laced boots. Were not the night so mild they would have caught cold instantly. But no woman, no decent human being, could watch such tiny creatures wandering alone in the night without intervening. As they approached the gate I leaned over it. “Dear children, where are you parents?”

“We’re looking for a mother,” the little girl replied readily.

“Hush, Lottie,” the boy said crossly. “You mustn’t blab our affairs all over.”

“It’s very dark,” I observed. “You must have walked a long way. I am Miss Halcombe, and I live in this cottage. Would you care to come in and have some refreshment? I can offer you some warm milk. It’s a favorite of mine. And perhaps some seed cake.”

“My name is Micah Camlet,” the boy said with dignity. “No, thank you.”

“Oh, but Mickey, I love seed cake,” Lottie cried. “And there’s a blister coming on my heel. I wish I had put on stockings, but you were in such a hurry.”

“Your legs must be cold. I must make up the fire to boil the kettle anyway. You are very welcome to come and sit by it. And I could look at your blister.” I unlatched the gate and held it invitingly ajar. “What is your name, little one?”

Trustingly she stepped in. “I’m Lottie. Pleased to meet you.”

Her brother, wiser as males must be even at his age, said, “We must not impose upon you, Miss.”

“How is it that your mother let you slip away without her, my dear?” The child put a thumb into her mouth but then, clearly remembering a nurse’s injunction, pulled it out again. Very gently I took the child’s free hand.

“We haven’t a mother,” Micah interposed.

“And we want one,” the little girl added. “Father Christmas was supposed to bring her, but he must have forgot.”

I drew them both onto the garden path, and was just making to latch the gate when there was a commotion farther down the road. There was a clatter of hooves, and suddenly a tall black horse loomed up out of the mist. Its rider was hatless, his long coat unfastened and billowing behind with the speed of his progress. Quite an heroical picture, spoilt only by the glint of steel-rimmed glasses on his face. “Madam, have you seen – great God. Micah! Lottie!”

“Is that your father?”

“Yes, and he shall be so cross,” Lottie said, with composure.

“He read to us about Father Christmas,” Micah objected, “so I don’t see his complaint.”

By this time the rider had pulled up at the gate and flung himself off his steed. “Children, are you hurt? How dare you give the slip to Nurse like that! It’s very naughty of you!”

He was, quite naturally, entirely beside himself with anxiety. In the role of peacemaker I said, “Mr. Camlet, I presume. And this is your son and your daughter? They do not seem to have suffered much from their adventure. A blister, I am informed, is all the souvenir –”

“How dare you meddle with my family affairs, woman? It cannot be quite respectable that you lurk in a dark garden like this.”

If he had been a big dangerous-looking fellow I might have spoken more softly, but all of this man’s height had been lent by his horse. Afoot he was not intimidating, certainly not with spectacles. “It is my own garden, sir, or rather the property of my hostess. If anything I am the aggrieved party. I did not invite you or your family to call. But I see that you cannot be reasoned with, and it is too late for conversation. Good night, Miss Lottie and Master Micah.”

“Pleased to make your acquaintance,” Micah said politely.

Lottie clung to my hand. “But we were going to have seed cake!”

Gently I extracted my fingers from hers and retreated into the house, firmly shutting the door. Peeping through the parlour curtain I saw the Camlet family in silhouette having it out with itself in the intermittent moonlight. My fear was that the father might be so intemperate and choleric as to beat his children. As their parent he had full right to chastise them as he would, but the sight would be lacerating.

But against that there was the children’s placid demeanor when they spoke of him. They had not been afraid in the least. Finally the taller figure lifted the smallest to the saddle and climbed up himself before giving the boy a hand up to the saddlebow. Thus burdened the horse turned slowly, walking back the way it had come. The thick hedge prevented me from seeing more. Sarah came through the gate half an hour later, full of chatter about hemming infant linens. I said nothing to her of my evening, and we went straight up to bed, I pausing only to scribble down this account. Of all the pointless encounters!